October 15, 2025

Duchovny, Hartley & New Criticism

“How soon unaccountable I became tired and sick,

Till rising and gliding out I wander’d off by myself,

In the mystical moist night air, and from time to time,

Look’d up in perfect silence at the stars.”

The above epigraph, taken from Walt Whitman’s “When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer,” was written in 1865 and originally part of Drum-Taps before its inclusion in Leaves of Grass. The poem is evenly split between the science lecture, with its charts, diagrams and figures, and Whitman’s disillusionment and retreat into the night to quietly witness the stars by himself. Sometimes, the poem intimates, quantification can reduce the true value of and appreciation for what is being studied.

It’s very easy to replace the learn’d astronomer of Whitman’s poem with the New Criticism and its mid-20th century “close reading” approach to literary critical appraisal. Although its existence has expired, its effects are still tangible. Louis Menand, in The Free World: Art and Thought in the Cold War, notes that it “continues to constitute the bedrock of the discipline of literary studies in the 21st century.” He explains that the New Criticism, filled with its own biases and agendas, imposed a set of rules upon the study of literature that disregards “the work as a reflection of the life of the author or the times in which it was written, the meaning the writer intended and the ideas they expressed, the way it makes us feel.” It allows for literary works, particularly poetry, to be dissected and subjected to scientific scrutiny without context in many universities.

Any critical theory formulates boundaries, and those created by the New Criticism for higher education English departments over seventy-five years ago has resulted in a potential rebuff for anyone daring to invoke the opinion of the writer, the least knowledgeable individual about the given text, or so we’re told. The infraction is less an anathema than a sacrilege against the literary criticism gods and as unforgivable as it is misinformed. But, then again, rules are made to be broken. Just ask a poet.

Whitman was a blatant rule-breaker, writing free verse in an era still largely conforming to strict meter and rhyme and exploring topics heretofore unexamined in poetic form. He was criticized by T.S. Eliot, an acknowledged influence on the New Critics, with whom Whitman reportedly also didn’t pass muster. But, as Whitman made clear, walking out on any astronomer’s lecture is always an option since poetry in recent centuries has favored a one-on-one relationship with an individual reader who chooses to wander off alone into the night air.

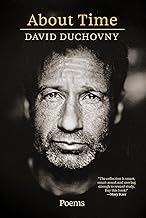

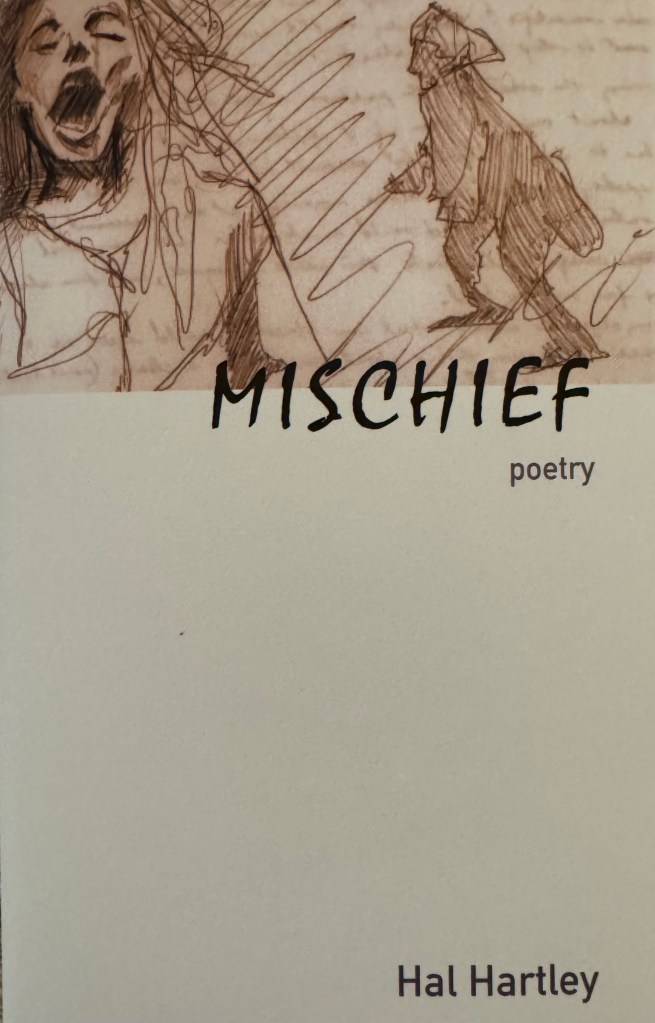

That relationship is encouraged in two recent books of poetry, David Duchovny’s About Time and Hal Hartley’s Mischief. The poems of these collections are shorn of any need for rules or critical systems denying the author. They are observations, contemplations, musings, if you will, that create a quiet dialogue between reader and author, between thought and response, comfortable with what they carry and what they convey.

Acting and directing in film and television for four decades, Duchovny began his literary career in 2015 with the publication of the first of five novels. Having originally considered a life in academia, he explained to The Believer in 2021 that he “wasn’t any one of a number of the teachers I’ve had who live and breathe this stuff and have a passion for criticism.” Now, after ten years of writing fiction, he’s waded into the holy lands of the New Critics by producing a volume of poetry under the rather apropos title of About Time.

It seems fitting that one of Duchovny’s professors while studying at Yale was Harold Bloom, an opponent of New Criticism’s anti-authorial stance who is name-checked in About Time’s introductory “A Poetic Autobiography,” where Duchovny quotes what poets have said about their craft to determine the meaning and purpose of the genre. What he arrives at is an amalgam of contradictions that he uses to classify his own work. “I offer these poems,” he explains, in “the spirit of uselessness and beauty. The spirit of memory and forgetting and of thresholds honored and crossed.”

The poetry of About Time concerns life and fleetingness, a gathering of personal moments and considerations the author anticipates will be familiar to his readers, and they are. “You know this phenomenon,” he states in “Drive,” and we do. Mortality, memory and nature are juxtaposed (“So the moon rises this morning…upward and closer, to the ever-ongoing reconciliation of loss”), life is examined (“I age like a tree, each new ring an orbiting armor”) and self-assessment offered (“You must approach me as you would a ruin, twisted logic riven in stone”), and we understand.

“I wish my father could read my books,” Duchovny told Literary Hub in 2021. “He died before I published my first novel…He loved writing and respected writers most of all…” Fathers have figured prominently in Duchovny’s film and literary work – Bucky F*cking Dent and its movie adaptation Reverse the Curse, Truly Like Lightning, The Reservoir, House of D and now About Time. And so it is that in “Dead Seven,” Duchovny imagines his deceased father as reincarnated, now a child learning “as he crawls, walks, runs into the walls of his newly unlimited understanding,” with his son’s “need for him transcribed into his imagined need for me.” As in much of Duchovny’s poetry, conscience and emotion are laid bare, eschewing Rimbaud’s notion of ‘I is another.’

Like About Time, Hartley’s collection contains its share of the personal and the observed, what its author calls “real life adventures,” “situations described or imagined,” and “some examination of conscience.” Any of these could easily apply to the director’s films or his novel Our Lady of the Highway or stage play Soon. All are examinations of the human condition, with or without a philosophical twist or a mischievous touch.

Some poems explore the existence of the filmmaker in the process of “organizing life and business to make pictures,” as the writing of poetry during the “waiting between” tends to “threaten this apparent motion.” Other poems offer life as metaphor (“This conscience of mine, as a roof built above an idea of myself, I pay for…”) or character sketches, like the elderly narrator of “Curmudgeon” (“motor skills loosening and objects drop like somebody else’s fault…”). Yet another muses about perspective (“no longer in the effort to facilitate the anticipated push and shove of the recognizable”), allowing one to consider if ‘real life’ and ‘imagined’ are permitted to be indiscernible, first and third person narrations interchangeable.

Mischief speaks loudest when language and situation are pushed to their limits, as in “Adventures in Reading,” in which time is folded into itself as a man reads a translation of a centuries-old account about a nun’s self-education while undergoing his own learning process, described here as “an audacity, a kind of violence.” And while he insists “there is no time without boundaries,” the poem seems to demonstrate otherwise. Selections like this, and there are plenty in Mischief, transcend the film world that is Hartley’s usual medium and are a welcomed and rewarding addition to his oeuvre.

The personal and autobiographical in About Time and Mischief recall the English Romantics, also considered dispensable by New Critics founders. Duchovny and Hartley would be as well. But that’s because schools of thought like the New Criticism and its brethren set up a cottage industry in the literary field, free to prescribe yet unable to participate. They remain the scientist to Whitman’s layman, the explainers to the world’s appreciators and, in Hartley’s terms, the Large One whose intermediaries “teach us to know more your largeness.”

About Time is currently available from Akashic Books. Mischief is currently available only to Kickstarter contributors to Hartley’s latest film Where to Land, with a general release date forthcoming.

Related Article

Leave a comment