Book Club Corner

The following reviews focus on the series of novels my Book Club partner Krissy and I have read recently. Some are by authors we had never read before, some by writers with whom we were already familiar. In several instances we read multiple novels by the same author to gain a wider perspective of his/her works. It’s our hope these commentaries can act as a guide for anyone who hasn’t yet explored their fiction.

May 8, 2025

Alex Michaelides

Alex Michaelides’s The Silent Patient is a novel about identities, about betrayal and about the sins of fathers. But that doesn’t take into account the allusions to Greek drama and myths, the use of art to both illustrate and inform or the structural ambiguity of the book.

The novel is about Alicia, an artist consumed by tragedy, and Theo, her psychotherapist intent on breaking down the silence in which she has shrouded herself. The narrative is a psychological dance, a pas de deux across a turbulent past and present for each. Its finale determines the future.

Well-written and entertainingly conceived, The Silent Patient was a bestseller upon its release in 2019 and deservedly so. For readers, its plot offers a challenge, its characters a temporary, intriguing acquaintanceship, its conclusion a disturbingly satisfying resolution, the very stuff that makes a book a great read.

April 20, 2025

Charles Soule

“Prophecy, of course, is all about time—knowing the future, and letting others in on it.” Arthur Krystal, The New Yorker January 27, 2025

The above quote is from a review of another book but can just as easily apply to Charles Soule’s The Oracle Year. The novel’s protagonist, musician Will Dando, awakes one morning with 108 predictions that, over time, are coming true. He posts select ones online, fulfilling Krystal’s criteria, and plummets into a turbulent existence as prophet and puppet.

As the title suggests, the book traces Will’s journey over one year as the Oracle, his public persona that elicits awe as much as it does contempt. He has help in his efforts to use the predictions as he sees fit, but so do those who attempt to track the true identity behind the title.

As a study of human behavior, the novel examines many of the ways people react to predictions – with fear or a desire for control/monetary gain, as a personal threat or a challenge. It’s also a statement on how we inhabit a world where privacy has been compromised, rendered futile if the ends are rewarding enough. Technology and belief systems, religious, political and otherwise, are seen merging into one monstrous entity that comprises the antagonist of the tale.

Those who wield their own power, like the U.S. government and the Reverend Hosiah Branson (who appears to have embraced rather than resisted the Seven Deadly Sins), are the faces of that entity, reducing Will’s predictions to life-saving wild cards in a game void of chance. The stakes are the lives of Will and his friends, a small circle swept up in a maelstrom of events set into motion by those very predictions.

But there’s also a lot to learn from the tertiary characters, the unnamed crowds and mobs and followers who worship or fear Will, who choose divisiveness over inclusion and who subscribe to destiny when things go awry. The last quarter of the novel is a demonstration of how the term “human folly” is redundant, with posturing, petulance and pride accurately serving the satire of the narrative.

The Oracle Year makes clear that such behavior is not the answer – sometimes it’s necessary to humble ourselves to make a difference. It’s one of the things Will learns in a well-drawn character arc in a novel about free will and being the sum of our choices.

For this site’s examination of Soule’s work on Daredevil comics, click here.

March 15, 2025

Stephen King

Last year, with the impending release of Mike Flanagan’s film adaptation of Stephen King’s “Life of Chuck,” we decided to read the short story collection If It Bleeds, which contains the Chuck narrative, tackling each of the four stories between the novels on our 2024 reading list. We discovered something we didn’t expect.

Three of the works in King’s collection of tales walk a fine line between psychological and supernatural, a balancing act not unlike television shows like Yellowjackets or the religion-vs.-science scenarios of Evil. The ambiguity created by this duality places more responsibility on the reader, inviting interpretation with no right or wrong answer. It might account for why “Life of Chuck” was our least favorite of the four stories.

“Chuck” is certainly psychological but unmistakably and primarily supernatural, with no attempt at balancing the two. Divided into three parts that telescope backwards, the portions never gel properly to produce a satisfying overall narrative, although the ingredients are more than capable of achieving that. “Chuck” was the first of the tales we read and it was a somewhat disappointing start.

“Rat” was a considerable improvement. So was the title story, closer to a novel in length and featuring King’s recurring detective Holly Gibney. The writing is so well crafted, the ambiguity so balanced that there’s more of an edge to the tales, leaving the reader to choose the meaning of each.

To our surprise, our favorite selection was “Mr. Harrigan’s Phone.” We were both familiar with the movie adaptation, but the story is better executed by aiming for a different audience than the film, containing as it does a subtext about our own attachment to and obsession with phones and a much more personable narrator.

If It Bleeds is a worthwhile collection. Now we’re just banking on Flanagan to put the pieces of “Life of Chuck” together more effectively.

Addendum: July 2, 2025

It’s nice to report that the film medium suits “Life of Chuck” well. A more cohesive version of the story, including a fully realized Act II, Flanagan’s movie adaptation employs much of King’s narration while supplementing visually, aurally and textually to connect the parts into a more complete portrait. We can call the short story a blueprint for a warranted film collaboration whose results now offer a moving précis of human life.

October 22, 2024

Wm. Paul Young

“Who wouldn’t be skeptical when a man claims to have spent an entire weekend with God, in a shack no less.” So begins Wm. Paul Young’s novel The Shack, which has sold over twenty million copies since its 2007 release. It became one of our 2024 selections through a recommendation by Krissy’s mom.

The true reward of Book Club is always the shared experience of reading a novel together while maintaining an individual relationship with it and exchanging ideas and interpretations throughout the process. The Shack managed to provide plenty of discussion.

The novel is a narrative of healing, of coming to terms with a traumatic moment, in this case the protagonist’s grief over the loss of a loved one. It utilizes the iconic Holy Trinity as a means of communicating its message but remains open to interpretation beyond its boundaries and into the realms of psychology, personal spirituality and even science. It appears to be a book in which the reader is responsible for determining how it should be read, depending on that individual’s experiences. And, whether or not you like what’s on offer, it generates conversation.

Krissy and I discussed the novel throughout our time reading it and afterwards, most of our talks focused on the book’s central metaphor. My experience was erratic and restless in contrast to Krissy’s appreciation, which remained consistent throughout. Overall, she felt comfortable with it, liked its sentiment, especially its decision to not press any one religion over another, and felt that it’s a work that can be beneficial for anyone who has been through a life trauma. She was also taken with the author’s intention to initially write the work for only his family and friends, only sharing it publicly after the urging of family members.

I spent nearly two-thirds of the book closer to the skepticism evidenced by the protagonist early on before discovering how I needed to approach it, to interpret it and to be comfortable with it. And while my regard for the book may not be quite as high as Krissy’s, we both agree it was an essential read.

September 3, 2024

Ernest Hemingway

In A Farewell to Arms, Ernest Hemingway’s novel set in World War I, the countryside of Northern Italy, including the mountains and valleys that serve as occasional battlegrounds, are rendered in journalistic prose typical of the author’s style. Like the Italian terrain in the book, the narrative has its own peaks and dips, an uneven assortment of moments that results in a disappointing read.

A century after Gertrude Stein coined the term “Lost Generation” for Hemingway and the other young artists and writers who witnessed the first of the world wars, A Farewell to Arms has not aged very well. Despite the author’s professed iceberg principle, in which the writer need only convey what is above the surface level and imply the rest, the characters here are one-dimensional at best. Emotions are reserved only for women, whose portrayal runs the range from unflattering to outright insulting. Women are hysterical, their male counterparts stoic. In this novel, men, particularly protagonist Frederic Henry, suffer from matter-of-factness and a Lost Generation malaise that transform even what should be exciting into the blasé.

Hemingway’s prose, which may once have been somewhat of a stylistic revolution, now appears stilted and repetitive, so that conversations are lackluster and descriptive passages tedious. Yet, the basic plot, the best feature here, manages to lift the book to at least a mediocre level with a bit of everything, including romance, intrigue, action and even tragedy. Unfortunately, it can’t overcome an emotionally vacant narration, making many of Hemingway’s short stories and later novels more appealing choices.

June 28, 2024

Georgia Hunter

Having discovered the Hulu series We Were the Lucky Ones, we were impacted enough to add to our reading list Georgia Hunter’s 2018 novel of historical fiction on which the TV show was based, inverting the way we normally approach a book and its screen adaptation. The result was the discovery of a well-written and fascinating true tale of World War II.

Hunter’s prose is poised and graceful, her sense of character impeccable. As a narrative, We Were the Lucky Ones is captivating, intricately weaving through the lives of the Kurc family from 1939 to 1947 as survival becomes its prime objective. As an historical work, the novel offers details of the Holocaust seldom considered in fiction. The rationing of food, loss of home and property, the danger of travel, of identity, of the whim of those in control are all part of the narrative about Hunter’s ancestors.

Hunter positions the family at the start and end of the book in normality, allowing the core of the novel to examine how their existence is plunged into an alternate world of hardship and hope. It was a mixture of both luck and cunning that allowed this family to defy the odds and avoid becoming part of the 90% of Poland’s Jewish population to be annihilated. Of the surviving 10%, the Kurc family comprised 3%.

This is Hunter’s first and only book but, based on her style and ability, we remain interested and curious about what her next project will be.

May 6, 2024

Mark Twain

Disclaimer: Controversy and criticism have always hounded Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. In 1884, the year it was first published, it was declared immoral and a bad influence on young readers. Today, the book has been branded racist for its demeaning portrayal of Jim and other Black characters. It should not be misconstrued that our intentions in reading/rereading and reviewing this novel constitute an acceptance or a condoning of such depictions. Our purpose was to examine the book for its literary value, largely through Huck’s inner journey as he physically travels further into “sivilization,” as Krissy’s evaluation below attests.

Introduction: Written in the 1870s and 1880s, Huckleberry Finn is set in the pre-Civil War, a choice that leaves it open to social commentary on the U.S. past and its shortcomings. According to the notes in the Penguin edition of the novel, Twain intended a different book in the early stages of writing, one in which Huck and the escaped slave Jim travel north into free states where Jim would be safe. But he halted work on the book in 1876 and, by the time he resumed three years later, “began to introduce new themes, new characters” and a new direction “down the Mississippi into territory where slavery existed in some of its worst aspects.” The change would permit Twain to explore social ills on a much wider scale.

Initially, reading Huckleberry Finn was appalling because of its derogatory language toward Blacks, the way they’re referred to as property and the general consensus among all characters that they are seemingly less than human. Despite this, I continued reading and came to realize this is a depiction of how society was at that time, so I was actually experiencing culture shock. Mark Twain himself notes at the beginning of the book how he thoroughly researched the dialects for the regions about which he wrote. He also would have been fully aware of the attitude of the population at the time.

Looking past the initial shock, however, there is a story of a young boy with a life riddled with abuse, extreme poverty and neglect. He is street smart, resourceful and resilient, although a bit gullible when it comes to some of his peers, and he and Jim are on a journey that will risk both of their lives for the sake of the latter’s future.

Throughout the book, Huck engages in an internal battle over what he has been taught about Jim and other slaves being nothing but property and that he would spend eternity in Hell by helping Jim escape. But through a series of adventures, he sees Jim for the sweet, nurturing, loyal person he is. Together, they weather so many storms, both literally and figuratively, in their journey to attain Jim’s freedom. It’s admirable.

March 9, 2024

Jonathan Swift

This is my second reading of the Jonathan Swift classic Gulliver’s Travels in forty-plus years and Krissy’s first, and it was a selection that sparked considerable discussion. It’s easy at times to feel as if one is misreading Swift and his arguments, but Krissy’s insights helped effectively tether the work and its perspectives.

The book is a travelogue divided into four voyages undertaken by Lemuel Gulliver, who is stranded each time in an undiscovered land where he learns about the customs of the inhabitants and how they compare to those of England and Europe. In essence, it’s a fantasy, but its satire is what saves the narrative from becoming too far-fetched, although, as Krissy notes, Gulliver returning home to England with evidence from several of the lands to which he’s traveled tends to stretch things to the other extreme and destroy the illusion created by each tale.

Swift’s talent was well-known during his time, this author, essayist and clergyman having penned a series of longer and shorter works inspired by and taking aim at political, social and religious issues of the era. Besides Gulliver’s Travels, he is probably best known for “A Modest Proposal,” a wickedly crafted essay mockingly suggesting that Irish children be served as stew to help families in Ireland offset the economic hardships inflicted upon them by the English.

Krissy points out that if you read Gulliver’s Travels, you’ll go small, big, paranormal and equestrian. The first and second voyages use the motif of size to illustrate its author’s intentions, from the smallness of the minuscule citizens of Lilliput to the largess of the towering Brobdingnagians. In the fourth voyage, Swift transposes the places of humans and horses, calling the former by the newly coined name Yahoos and allotting them a subservient role to those of the Houyhnhnms, the ruling class of the much more graceful horses that occupy the land. Only during the third voyage does Gulliver interact with humans his own size and with concepts as inane as possible. And it all becomes a lesson about humanity.

Yet, while the nobler characters Gulliver encounters in the form of the Brobdingnagians and the Houyhnhnms are a clear contrast with human behavior, they are still capable of acting less than moral, fair or ethical at certain times. If the reader applies those values, however much Swift may demonstrate how easily each can be corrupted for selfish ends, the result is less than a perfect score for even these two societies when it comes to specific practices and outlooks. But maybe that’s the author’s point about any society.

In each of Gulliver’s voyages, Swift seems to be readjusting our comfort zone about what it means to be human, holding as ‘twere the mirror up to nature and forcing us to examine our patterns, habits and cycles and, most of all, our tolerance of the absurd, the appalling and the profane. Gulliver’s Travels doesn’t merely mock, it clamps down and bites. Since much of what Swift jabs at and skewers in the course of 250-plus pages is still present today, there is ample evidence that history does indeed continue to repeat itself. And with an additional several centuries of hindsight since GT was first published in 1726, the modern reader has an abundance of historical examples to defend that notion.

While reading Gulliver’s Travels, we posed the question: What would Swift be writing if he were alive today? It might be something like the book the title character of Baumgartner, Paul Auster’s latest novel, is working on, a piece “in the spirit of Swift,” just one of the “intellectual pranksters who have turned the world upside down in order to make their readers stand on their heads and try to reimagine a world that is right-side-up.” It seems no coincidence that Baumgartner’s book is divided more or less evenly into four parts like Gulliver’s voyages. And how successful would Swift be as a writer today? As Auster’s novel notes, “sadly, these are not the happiest of times for satire, and it remains to be seen if anyone gets the joke.”

January 18, 2024

Charles Portis Redux

Our previous encounters with Charles Portis novels (see below) focused on Masters of Atlantis and Gringos, his final two works. This time around, we chose his first fiction after he traded in his journalistic job with the New York Herald Tribune in 1964 for a career as a novelist and a reputation as the king of quirky. Norwood is true to the author’s other books we’ve reviewed, character-driven and eccentrically and endearingly populated, not so much exciting as satisfactory and with the concept of “family” at its center.

In addition to its title character, Norwood Pratt, the novel features a charming and comedic cast, including Vernell, Grady Fring, Rita Lee, Edmund B. Ratner and Joann, who appear in an entertaining journey from the South through the Midwest to New York City and back, all of which is set in motion by Norwood’s obsession to collect on a $70 debt.

Norwood is Krissy’s favorite Portis novel so far (we still have two of the five to read), largely due to her love for the characters. The ending could have tied up a bit better (the final thirty pages seem somewhat rushed), but the narrative otherwise flows nicely. We both find that Masters of Atlantis has a better storyline, but Norwood has more lovable characters that propel the narrative. And, as Krissy points out, how could anyone not love Norwood after he rescues Joann? Portis also seems to have set himself up for an unwritten sequel based on a second debt owed to the title character by the end of the novel.

Norwood may not be the smartest tool in the box and mistakenly believes himself to be a Casanova, but he’s caring and determined. His unpredictability is a large part of the humor, and every other character on this oddball adventure is given an opportunity to set him up to deliver a punch line. And, as Kirkus Review notes, “Norwood is just simple enough to be believable.”

We highly recommend giving this book a read. There’s no doubt you’ll fall in love with these personalities along the way.

January 1, 2024

Kazuo Ishiguro

In his 2008 Paris Review interview, Kazuo Ishiguro spoke of using a butler as protagonist in his novel The Remains of the Day as a metaphor for “a certain kind of emotional frostiness. The English butler has to be terribly reserved and not have any personal reaction to anything that happens around him,” what he called “the universal part of us that is afraid of getting involved emotionally.”

The novel, despite its historical backdrop of England between the two World Wars, is a remarkable study, characterized by Krissy as a tragedy, of a butler named Stevens, who spends a mid-1950s trip through the south of England narrating, musing and reminiscing about his years as a servant. In fact, our focus was initially on the historical implications until the last several chapters when the past dissolves into a clearer picture of the present Stevens.

The story unfolds slowly and largely in retrospect and, while not much actually happens, the narrative is consistently intriguing because there’s a fascination with Stevens’s telling of the tale, however unreliable or contradictory he is throughout. Possible conditioning from his father has him falling prey to the idea of being a perfect servant and complying with his employer’s needs while losing sight of human dignity in the process. It’s evident in his aloofness with others’ emotions as well as in his somewhat star-crossed relationship with co-worker Miss Kenton. And it’s apparent that the reader is more cognizant of romantic tensions than Stevens.

Ultimately, it’s the way Ishiguro intentionally withholds the first names of his major characters, weighing them down in formality, that removes any chance of warmth or familiarity between them. The same is true of the relationship between Stevens and the reader, so that all we can hope for is a better understanding of the narrator at the expense of any emotional attachment. The fact that it works so well is a credit to Ishiguro’s ability to suspend the reader’s judgment in favor of simple observation.

December 1, 2023

Paul Auster

Paul Auster’s 1994 novel Mr. Vertigo, about the rise and fall of the late 1920s fictional levitating/flying phenomenon Walter “The Wonder Boy” Rawly, is a mesmerizing read that examines life and its choices in the 20th century as Walt mirrors the periods in America during that time, gliding from the Roaring Twenties and the Great Depression to World War II and post-war automation and suburbia.

Auster’s reputation as a notable contemporary American author was cemented with such works as The New York Trilogy and The Music of Chance and reinforced by more recent releases like 4321, but Mr. Vertigo is an overlooked gem, one of those novels that deserves the attention the aforementioned books receive. And its unusual mix of Spinoza, Huck Finn, Sir Walter Raleigh and Dizzy Dean makes for an intriguing read.

Walt ascends, both figuratively and literally, to celebrity through his trainer, mentor and friend Master Yehudi, a Hungarian Jewish immigrant who, along with his aggregate of the indigenous Mother Sioux and a Black orphan named Aesop, becomes Walt’s surrogate family and his first life lesson. Krissy and I found ourselves becoming most attached to Aesop and Mother Sioux and their relationship with the newcomer as they gradually earn his love and respect. In discussing the novel with I.B. Siegumfeldt for A Life in Words, Auster noted that “tolerance and equality are the bedrock on which everything else is built.”

The language of the book is crude, raw and freewheeling, what Auster described as “a semi-insane American vernacular, common speech shot through with biblical phrasing,” and it moves the narrative along at a brisk pace, traversing the U.S. and detailing Walt’s growth as a character. The story is an emotional road trip, funny as much as heartbreaking, frightful as much as comforting. It kept us guessing and had us interpreting metaphors and allegorical implications of the character and his times, even when it suddenly took a hard left turn into a perfect second half that couldn’t be predicted. It’s a narrative that works and a satisfying read.

At the heart of the novel, however, is the title character, an antithesis of sorts to Walt’s Wonder Boy. Mr. Vertigo is the grounded, non-powered Walt who is just like the rest of us looking for a place in the world and an identity with which to share it.

In A Life in Words, Auster refers to Mr. Vertigo as a myth, explaining that “levitation is a metaphor,” and further explaining that flying is “connected to the desire for transcendence in all of us, the desire to do something extraordinary, to make something beautiful.” Mr. Vertigo attests to that.

November 17, 2023

Edgar Allan Poe

Mike Flanagan’s inventive melding of Poe’s classic short stories and poems into the Netflix series Fall of the House of Usher was the inspiration for us to read the author’s only novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket. Published in 1838, the book’s seafaring theme fit comfortably with the nautical tales popular during the early 19th century, predating Herman Melville’s Moby Dick by over a decade.

The novel has eluded a generally accepted interpretation since it first appeared, but Krissy and I found its tale of loss to be reflective of Poe’s grief over the deaths of his mother, foster mother and, particularly, his brother Henry, who had died seven years before the novel’s publication. If the narrative was a way to cope with his losses, Poe still managed to create an alluring story filled with the familiar tropes with which he is associated: psychological terror, suspense and even horror.

There were several agreed upon flaws in the book, including a series of digressions that inform the reader of standard shipping practices, geographic peculiarities and other sundry facts, but Krissy was able to look past them easier than I could, remaining very fond of this high-seas adventure because it creates and maintains for the reader an essential emotional connection with its lead characters. And that connection is what propels an exciting narrative fraught with peril, filled with daunting moments and featuring a suspicious supporting cast of characters. Overall, that’s rather good for what Poe dismissively called “a very silly book.”

October 20, 2023

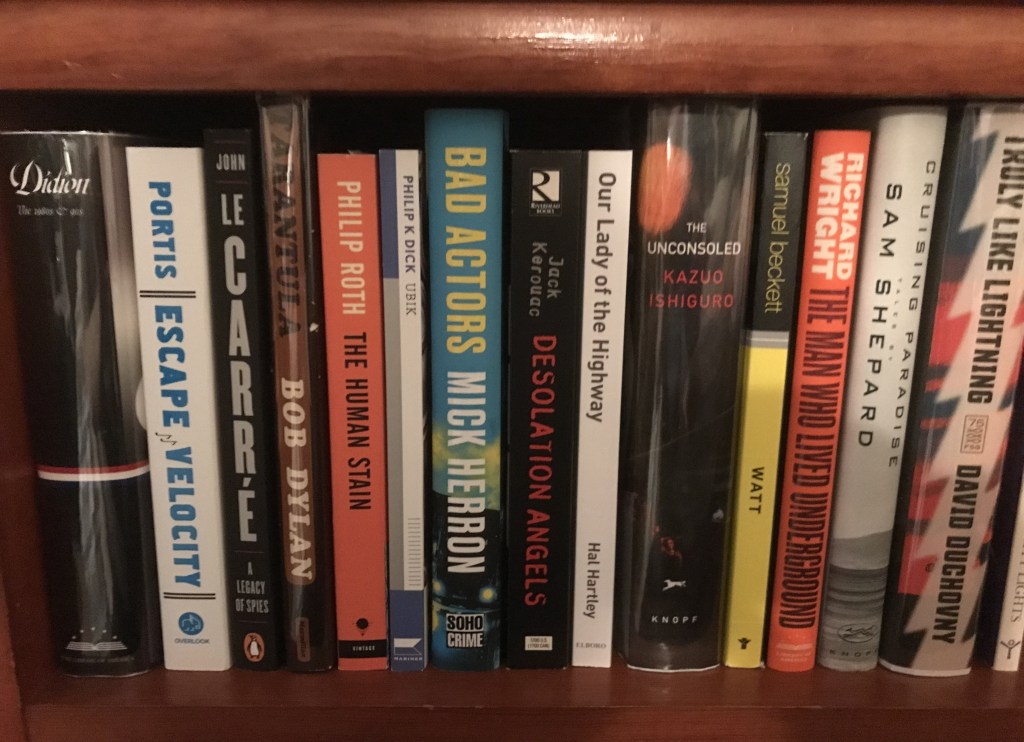

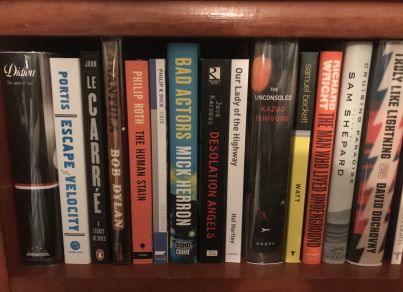

Philip K. Dick, Mick Herron & Charles Portis

Neither of us had read any of Philip K. Dick’s fiction when we undertook The Transmigration of Timothy Archer (1982) as the first novel for the Book Club. Dick is probably most familiar to many through the film adaptations of his works of science fiction: Blade Runner, Total Recall, Minority Report and A Scanner Darkly, to name a few. But Timothy Archer is anything but sci-fi.

An examination of mortality through religious, philosophical, spiritualist and New Age means, the book is set in the aftermath of John Lennon’s murder in 1980, establishing it as a metaphor before flashing back through the life and losses of the protagonist, Angel. Her relationships guide the reader through the novel’s explorations of coping with the ephemeral.

The philosophical is replaced by the political in PKD’s 1962 novel The Man in the High Castle, a what-if scenario of life in the U.S. had the Axis powers won World War II. Here, the author’s study focuses on humanity’s fear of the Other and its tendency to subordinate difference. And the book’s use of the title character, hidden for most of the novel, as truth-bearer is inspired. But we would caution anyone choosing to watch the Prime Video series adapted from the book to beware – the characters’ names are retained but the storyline isn’t.

As we’ve come to recognize, a PKD novel is a journey. His ideas provoke the reader into deeper thought about the eventual big picture being painted, and he dodges and weaves until the very last page so that you’ll be pondering it for days after. Sometimes, however, this comes at the sacrifice of character detail and lack of insight of the female psyche. In Timothy Archer, for example, he attempts to tell the story through the female point of view, but the masculinity shines through.

PKD’s focus is on message and plot, his characters serving each well, but their purpose is exhausted once the point of the book has been made. He’s an author of ideas, and readers interested in following the maze of concepts or conspiracies should enjoy these two works. For fans of character-driven novels, Mick Herron might be a better choice.

Although Herron is best known for his Slough House spy series, we selected Nobody Walks, his 2015 mystery novel containing a bit of conspiracy and only a dash of spies. Herron prefers his narratives, so fluidly and intelligently written, to be woven from characterization, and this novel illustrates why many consider him to be le Carre’s successor.

While recent mystery novels such as Fuminori Nakamura’s My Annihilation tend to fall short of their promise by attempting to be a little too clever, Herron applies old-school techniques to a digital world with satisfying results. His exposition slowly unravels the possible suspects in the death of protagonist Tom Bettany’s estranged son in the same way Bettany’s own background is gradually divulged until all the chess pieces in a plot reminiscent of a simultaneous exhibition are ready to be maneuvered.

The cast of personalities Bettany encounters alternately advance to and retreat from the truth, keeping the reader off-balance. Herron has an uncanny ability to make every character introduced in his novel a viable suspect, yet, as backgrounds unfold, he continues to withhold crucial information about Bettany’s son. Like any good mystery, Nobody Walks holds its cards close to its vest.

While reading the book, we sat and discussed a multitude of possibilities only to discover we were both wrong by its conclusion. You might want to try your hand at solving Herron’s puzzle.

Charles Portis, best known as the author of True Grit, was another newcomer for us. He’s been called “the best American writer you’ve never heard of,” but it may be time for his anonymity to be revoked.

Our Portis choices were Masters of Atlantis (1984) and Gringos (1991), his final two novels before retiring from writing. His books are populated with more than a few slightly oddball characters whose place in the world isn’t always so easy to pinpoint. And that’s what makes the underlying commentary of his novels so unassumingly charming. As a reporter, Portis was an observer, a witness to humanity, and his characters pick up where real life leaves off.

At heart, Masters of Atlantis’s Lamar Jimmerson and his Gnomon Society, a 20th century fraternal order that preserves the sacred texts of Atlantis, are a cross-section of humankind, Everymen whose lives are spent in a belief system they protect and defend and for which they sacrifice. Their eccentricities propel the novel and make their inability to discern fact from fiction forgivable. Portis maintains a genuine affection for his characters and chooses not so much to abandon them by the book’s end as release them.

Lamar and his followers aren’t much different from Jimmy Burns and his rag-tag team of largely American expatriates living among the remnants of Mesoamerican civilization in Gringos. Caught between the phantom beliefs of an ancient past and the unpredictability of the future, they are connected by a quest for any certainty that will provide meaning. Portis does require patience of both his characters and his readers, particularly during his 150-page exposition in Gringos, and while the novels might reveal themselves slowly, they reward most generously.

Leave a comment