July 9, 2024

CSNY ’74: See the Sky About to Rain

This summer marks the 50th anniversary of Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young’s monumental reunion tour, which included a concert at the Atlantic City Race Course in Mays Landing, one of two New Jersey sites to play host to the group in 1974. And that show, rather than becoming a forgotten footnote in CSNY’s career, has surprisingly remained a lasting memory for the musicians and their chroniclers, although not necessarily because of the performances that night.

The quartet’s collective touring absence from 1971 to 1973, usually credited to clashing egos, had created an overwhelming demand for a reunion by 1974. There had been the occasional set in which all four shared the stage at one of their solo or duo concerts, but a full-fledged reformation of the lineup had eluded them until several months before they would take to the road as a band once more.

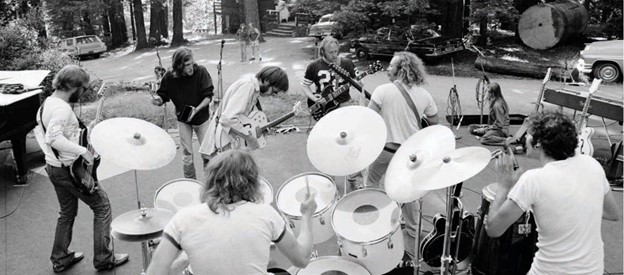

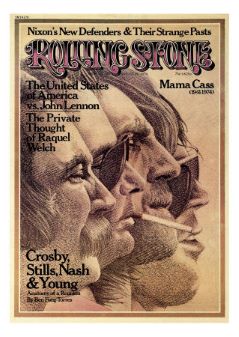

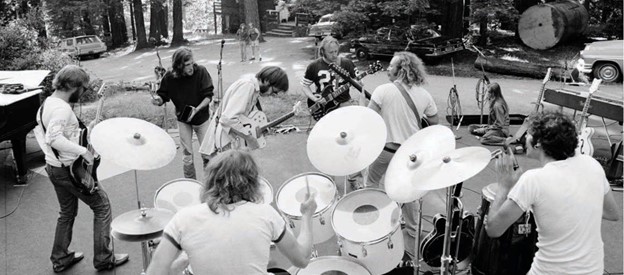

Talks about a reunion were completed when Young agreed to rejoin the flock in spring 1974 and, according to Ben Fong-Torres’s cover piece in Rolling Stone’s August 29 issue that year, “offered his ranch, nestled in the redwoods, as rehearsal quarters, six days a week through the month of June.” Three weeks in, Stills told Crawdaddy magazine, “we get out there…and play for about four or five hours a day. We haven’t done the old songs in years, man, it’s almost like playing them for the first time…And there’s plenty of new songs, too.”

The group rehearsed outdoors on a forty-foot stage built in a grove to pre-create the conditions they would largely be playing in at open-air stadiums and the arrangement attracted a smattering of unexpected fans listening from afar. In 2014, Rolling Stone ran an online article titled “The Oral History of CSNY’s Infamous ‘Doom Tour,” in which photographer Joel Bernstein described the atmosphere created by the band rehearsals at Broken Arrow Ranch that June: “Word got out about the rehearsals They had a PA set up and they’d rehearse Monday through Friday. The sound travelled for miles, throughout the hills. I started seeing people who were walking down the road from all over. I picked up a hitchhiker that had flown up that morning from Burbank Airport to try and listen…They just climbed the hills, got high and listened to everything. It was wild.”

The massive crowds would begin arriving with the start of the tour on July 9, when, on what Cameron Crowe describes in the October 1974 issue of Crawdaddy as “a grey, rainy day,” CSNY regaled those in attendance at the indoor Seattle Coliseum with all forty-four songs they had in their repertoire, resulting in Crosby overworking his voice. At the second stop of the run in Vancouver, Fong-Torres reported in Rolling Stone’s August 15 issue that backstage Young complained the now slightly trimmed set was “still too long” and that the concert “should revert to the old CSNY formula – acoustic, electric, finish” rather than two electric sets bookending an acoustic portion. That didn’t happen.

The idea of playing football stadiums wasn’t new in 1974. The Beatles had done it a decade earlier and apparently Stills and Young favored playing venues that large for the reunion tour. According to David Browne in his Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young biography, “Crosby and Nash were less than enamored of the idea of playing stadiums but went along with the plan.” Despite such early discontent, the tour’s west-to-east trajectory played out over the next two months with a brief respite before performing a one-off concert at Wembley Stadium in London and subsequently abandoning the highly touted plans for a reunion album.

Those interested in experiencing what a 1974 CSNY concert was like can give a listen to the 40th anniversary souvenir 3-CD/DVD set released ten years ago, which is a worthy effort to recreate what would essentially be a standard set list of a show. But anyone who wants to explore the musical progression of the tour should turn to the wealth of audience recordings from that summer which capture the acoustic rarities in song and instrumentation from night to night, the changes in energy that accompany each show and the moments of brilliance that were achieved on a given evening.

According to the Sugar Mountain website, of the thirty-one concerts on the CSNY 1974 tour, there are twenty-one complete or partial audience recordings streaming and circulating. Unfortunately, the Atlantic City Race Course show is not one of them. The lack of an audience tape of the show means that reliance is placed on verbal and written accounts, some accurate, some mistaken and some apocryphal, and risks a legend becoming large enough to amass a considerable amount of hyperbole.

Five years before CSNY appeared there in 1974, the Race Course, which originated as the Atlantic City Race Track in 1946 and is located approximately thirteen miles west of the city that bears its name, had been the site of the pre-Woodstock Atlantic City Pop Festival, an event CSNY had been scheduled to play before their appearance was canceled. The festival propelled Hamilton Township residents into a three-year battle for an ordinance “forbidding all future pop festivals in the township,” according to the Vineland Times Journal on August 7, 1974. It was overturned by the New Jersey Superior Court, but the township succeeded in securing a law in 1972 which mandated that such events have “police and fire protection, medical stations with a minimum number of nurses and doctors, waste disposal facilities” as well as a list of other requirements. The CSNY show would be its first test, but with a 4-H fair scheduled on the night of August 9 several miles from the concert, residents were still wary.

The Race Course concert seems to have originated with local promoter Electric Factory’s early plans to stage the show in Philadelphia at the 100,000-seat JFK Stadium on August 18. The venue was listed on tour itineraries but never advertised and was soon dismissed altogether, apparently in favor of the much smaller Atlantic City Race Course on Friday August 9. Whether or not JFK Stadium’s capacity, along with what was then a highly priced $10 ticket for general seating, proved too intimidating at a time when stadium shows hadn’t yet made their mark has never been confirmed.

The 1974 CSNY reunion has been called by manager Elliot Roberts, in the oral biography Bill Graham Presents, “the first pure stadium tour,” a claim that falls just a bit short of being completely accurate. “We played thirty-five stadiums,” Roberts is quoted as saying, but the fact is that, while there were thirty-one concerts, only twenty-four cities were on the tour itinerary, sixteen of which presented stadium shows with the remainder relegating the concerts to arenas or raceways with much smaller capacities.

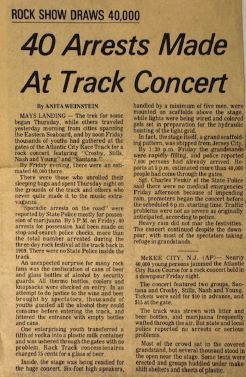

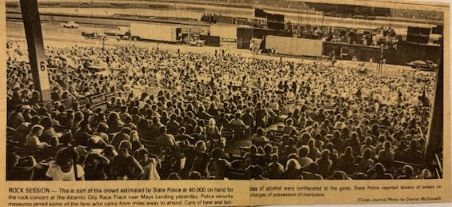

Several days prior to the Atlantic City Race Course show, local newspapers predicted 50,000 fans would converge on the venue, which online sources identify as having had a seating capacity of 10,000 and standing room for 25,000. According to local reports, actual turnout was estimated at 40,000- 42,000. Over the years, however, various sources have increased both the attendance and, in turn, the capacity of the Atlantic City Race Course to 50,000, 60,000 and even 70,000, all of which are highly inflated figures that propel the art of myth-making.

The lengths of performances also reached legendary proportions over the decades, in part due to Crosby’s exaggerations in interviews. Except for several shows on the tour that lasted four-plus hours, including the opening and closing U.S. performances in Seattle and Long Island respectively, the concerts usually clocked in between two-and-a-half and three hours according to extant audience recordings. Crowe reports that, in the dressing room following the Seattle concert, the band had already entertained “doubts about the potential effectiveness” of a four-plus hour show and discussed trimming the set “to an airtight three hours.” But various exaggerated statements and reports over the years have most of the shows lasting anywhere from four to six hours, including the Mays Landing concert, which was far short of those lengths.

Venues, attendance and performance length, however, weren’t the only items vulnerable to contradictory information. In the initial volley of post-concert reports from local press, gatecrashing was not mentioned amid a wide range of goings-on at the concert site that day, including arrests for drug possession and treatment for minor injuries. And from the grandstands, there were no signs of forced entry in evidence. Yet Peter Doggett’s account of the Atlantic City Race Course show in his 2019 biography of the group, CSNY, informs readers that “several thousand [fans] scaled the fences and gained access for free.” Gatecrashing did, on a large scale, occur at the 1969 Atlantic City Pop Festival, but the 1974 show was declared by the Times Journal “an orderly concert” with “no major outbreaks of violence.” The Philadelphia Inquirer the day after the show, however, reported that racetrack officials estimated that 5,000 fans “scaled the fences.” Which is accurate will remain a mystery. There is one thing, though, agreed upon by all who participated or attended, one factor that conjures immediate memories with no fabrication or embellishment, and that would be the weather.

When tickets for the concert first became available, no one could have predicted that President Richard Nixon, then in the throes of the Watergate scandal, would resign on the night of August 8 just before CSNY took the stage in Jersey City. Doggett reports that “CSNY opened their [Jersey City] show with ebullient spirit, dedicating ‘Love the One You’re With’ to incoming President Gerald Ford.” Six nights later, Neil Young would perform a new piece, “Goodbye Dick” in Uniondale, New York. Young’s sentiments seemed to hover more prominently in Mays Landing on August 9, an overcast day that threatened rain and no sign of goodwill toward the country’s new leader. According to the Times Journal report, “youths added their thoughts by plastering Nixon graffiti on racing bulletin boards,” while cries of “Impeach Ford!” could be heard throughout the afternoon.

The concert had been scheduled to commence at 5 p.m. on August 9, 1974, with Jesse Colin Young opening the festivities, but his cancelation left only two acts to perform that evening. The rain that had been looming since morning first arrived in the form of a drizzle as Santana appeared on the canopied stage around 5:30 p.m. Fans standing on the track in front of the band had already been firmly reprimanded by tour organizer/impresario Bill Graham for throwing frisbees near the musical equipment and now braced themselves for whatever the elements had in store over the next few hours.

CSNY finally took the stage at 8:30 p.m., with Crosby, Stills (clad in a Philadelphia Flyers jersey), and Nash centerstage and Young behind the organ, accompanied by bassist Tim Drummond, drummer Russ Kunkel, percussionist Joe Lala and a steady, incessant torrent of rain. As Doggett describes it, “the event turned into an ordeal by summer storms, which drenched the three thousand or so fans who camped out to secure places in front of the stage… The audience improvised canopies to protect themselves, as the weather set in and CSNY took the stage.”

Those who chose instead to sit in the grandstands sacrificed close proximity to the musicians in favor of remaining dry. Their experiences differed drastically from those who opted to view the concert directly in front of the stage. In a September 2012 online article in Atlantic City Weekly, Tim Wilk reports that John Scanlon, who in 1974 was “a 22-year-old newspaper reporter from Gloucester County and a big Neil Young fan, attended the concert with two friends.” Scanlon described the area in front of the stage that night as “a quagmire of mud and water. Everybody had to stand; there was no choice about it…the show became secondary.” He summed up the experience by stating, “The outdoor setting made the acoustics lousy, the noise in general made it hard to hear and the people trying to flee the elements were a huge distraction.”

Protected from the rain, those in the grandstands heard a fairly good mix of the sound and no extraneous noise or distractions. After all, as Johnny Rogan’s biography Neil Young: Zero to Sixty notes about the tour, audience recordings of concerts “confirmed that the sound quality was excellent for an outdoor gig” and seating at venues was “available for anybody who wanted them,” as fans at the Race Course fleeing the rain-soaked area in front of the stage for the shelter of the grandstands discovered. They were able to watch the remainder of the concert on television monitors used for the horse races at the track, a primitive precursor to today’s video screens.

Regardless of where fans had positioned themselves that night, it did not take long for the rain to become the most talked about factor. One month after the South Jersey show, Crosby told the New York Times, “For me…the best concerts‐on the tour have been the indoor ones…We can get ‘em off harder indoors, with the acoustic part of our set. But then again, in Atlantic City, the crowd stood outdoors in the rain for six hours [sic] and sang along with us more than anywhere else on the tour.” Nash revealed in Dave Zimmer’s biography of the group, Crosby, Still and Nash, that there was talk of canceling CSNY’s set on August 9 because of the weather. “We were advised not to go on,” Nash said. “But we looked out and saw 70,000 [sic] kids sitting there waiting on us…So despite the rain, we went out and played our hearts out. We never felt so loved.”

Young commented on the Race Course show fifteen years later while performing at the short-lived outdoor Bally’s Grandstand in Atlantic City on June 10, 1989. “I was here a long time ago,” he told the crowd. “It rained like hell through the whole thing.” And Stills called the 1974 South Jersey concert “fabulous” in an interview with Atlantic City Weekly in 2011, finding it “astonishing that I remember the show, because it was at a racetrack, and it just rained cats and dogs.”

In Doggett’s book, Crosby revisits that night, saying, “By the time we came on, [fans] were soaked to the skin, but they stayed for another four hours [sic] and sang along on all the songs. Man, that really moved me. I almost cried.”

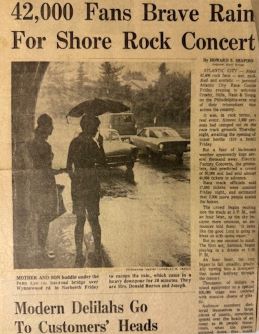

“42,000 Fans Brave Rain for Shore Rock Concert” the Philadelphia Inquirer headline read on August 10, with the article’s lead paragraph sporting words like “wet, muddied and ecstatic” to describe the crowd. It’s interesting to note that the group would once again play in the pouring rain on September 2 at the open-air Varsity Stadium in Toronto. The media at the time chose to focus on the music over the weather, one review mentioning the rain near the conclusion of the article. But, after fifty years, the weather conditions of that August night at the Atlantic City Race Course has remained the legacy of the show, regrettably superseding the music performed there. In fact, Stills is the only member of CSNY to comment on the actual performance that night, telling Atlantic City Weekly, “we were great…we really felt ourselves come together as a band…we played until we were going to get electrocuted and we had to stop.”

Audience recordings of the group’s other shows from that week, including the Boston Garden concerts on August 5 and 6 and Jersey City on the 8th, verify Stills’s comment. It was a week of peak performances, which may have prompted CSNY’s decision to professionally tape a series of concerts shortly after the South Jersey show.

Performances in New York, Landover, Maryland, Chicago and the lone overseas show in London on September 14 were recorded on multitrack tape, with the U.S. concerts captured across eight shows at Nassau Coliseum, the Capitol Center and Chicago Stadium from August 14 to August 29, according to online sources. Recording began five days after the Atlantic City Race Course concert, following the Buffalo show on August 11. These tapes were used to compile the CSNY 1974 CD set.

That release recreates what were largely a fairly consistent set list of electric performances on the first and third discs, with titles like “Ohio,” “Wooden Ships,” “Pre-Road Downs,” “Almost Cut My Hair” and “Helpless,” but the acoustic sets were more spontaneous in song selection during solo performances and in accompaniment during collective offerings. The spots afforded Young the opportunity to premiere a considerable amount of new material he carried with him on the tour, including “Love Art Blues,” “Hawaiian Sunrise,” “Human Highway” and “Star of Bethlehem.” “He hit a writing spell that was unbelievable,” Nash commented to Rolling Stone’s Andy Greene in 2014. But the acoustic sets also gave Young the chance to reimagine some of his older tunes.

For some, what remains the most vivid moment of the Atlantic City Race Course concert was the conclusion of the acoustic set. Forsaking the usual band arrangement of Young’s “Only Love Can Break Your Heart,” the rendition that night consisted of only an acoustic guitar and vocals.

With Young seated and Crosby and Nash standing behind him, the trio offered up the most exquisite three-part harmonies that were meant to end that portion of the set in style. However, it did more than that, eliciting an overwhelming standing ovation reserved for concert finales. Instead of commencing with the second electric set, Crosby, Nash and Young conferred for a moment and then resumed their places to perform a tour rarity, “Sugar Mountain,” as another vocal tour de force.

Some fans who attended that concert may insist the phantom strains of those harmonies still echo from the abandoned site of the now shuttered Atlantic City Race Course. But we’ll let Young have the last word on that. On the night of August 9, 1974, framed by his bandmates and looking out on the relentless downpour that nearly cancelled the show, he sang, “it’s hard to leave the traces for someone to follow.”

Leave a comment