February 1, 2025

Daredevil @ 60: Part 4 – Miller’s Elektra

A look at the character’s origin and early years in comic books.

In 2024, the image of Marvel comics assassin Elektra Natchios appeared on cans of Coca-Cola, her gaze penetrating as she brandished her trademark sai, a three-pronged dagger, in each hand. The choice was bold, unsettling yet alluring, very much like the character herself.

Today, Elektra has become the female Daredevil, sporting the moniker “Woman Without Fear.” She has her own ongoing comic book title and has become a semi-regular partner of Matt Murdock’s alter ego. But roughly forty-five years ago, she made her comic book entrance as a seasoned warrior, an assassin-for-hire, a former lover-turned-foe of The Man Without Fear.

According to Sean Howe, Miller’s intentions were to transform Daredevil into a more “lighthearted” version of previous writer Roger McKenzie’s run, but the introduction of Elektra, who Brian Nelson reported had already “been in [Miller’s] head for sometime before that,” changed that. “Her presence led the whole series down a very dark path,” Howe reports Miller as saying. “Because I was a kid in my twenties, and making up a sexy killer woman, it was bound to get pretty grim.”

Elektra’s name derives from the vengeful daughter in the Greek tragedy The Oresteia, her characterization based upon Sand Seref, a Will Eisner creation for The Spirit comics of the 1940s and her look inspired by bodybuilder Lisa Lyon. Miller acknowledged in The Daredevil Chronicles the distinctions between Lyon and his character: “Elektra doesn’t have Lisa Lyon’s skeleton, she’s larger, but she does have the details of a bodybuilder.” It might explain the 1983 edition of The Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe’s description of her as being a non-Lyon 5’9” and 130 lbs. It also reports that her “current whereabouts are unknown.”

As the daughter of a Greek ambassador, she first met and became romantically involved with Matt Murdock in New York City while they were in college. After her father was inadvertently killed in a kidnapping, she trained in the martial arts in Europe before serving the secret ninja order of the Hand and becoming a mercenary.

The loss of her father and her subsequent plunge into violence have spurred considerable speculation over the decades, beginning with how the character mirrors her namesake. Larisa A. Garski and Jennifer L. Yen, who see her as “awash in contradiction,” note that the trauma of her father’s death “pushes her toward the role of assassin that is not in total alignment with her core self.” Evidence of that core self can be seen in her choice to spare Foggy Nelson, the act that initiates her downfall. Paul Young has written that “Elektra is not just avenging her father; she is avenging her lost self, the possibility of a mature and self-determined identity she lost when her father died.”

Her creator also weighed in on the character, telling Peter Sanderson that “she was designed around her name,” which “has come to represent an entire psychological phenomenon.”

When Sanderson asked why Elektra simply doesn’t avenge her father’s death instead of becoming a mercenary for hire, Miller explained, “Basically there are years of corruption. Step by step, she has lost the belief that she and Matt held at the same time and more or less strayed from the righteous path. Her problem is that she’s not a good girl gone bad; it’s that she’s one of the villains whose got a weak streak in them.”

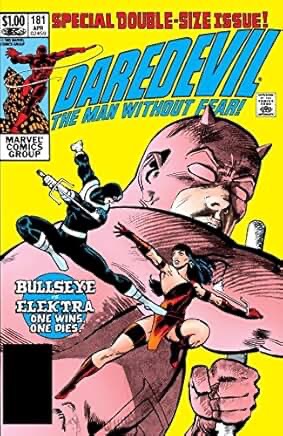

Miller never meant for Elektra to last long in Daredevil, but her presence would continue to haunt the title long after her death at the hands of Bullseye in issue #181. Her brief time in the comic book became a study of a hardened assassin still in love with Murdock, enough so that she spares Nelson’s life at the risk of her own life. Her death is something from which Murdock would have considerable trouble recovering.

It’s fair to say that Elektra came to define Matt Murdock/Daredevil more discernibly than any other antagonist because she is more than simply a villain. As a previous lover to Murdock/Daredevil, yang to his yin, she represents possibly the most complex relationship Murdock/Daredevil experiences simply because they are opposites attracting. His sense of justice as both attorney and vigilante compels him to battle her legally and physically, all the while violating the love and passion he still has for her, something that supersedes even the drama of his Catholic guilt and his own duality. She adds depth and complexity to Daredevil’s already contradictory nature so that, as Young poses, she “presses on the central paradox of Murdock’s character harder than anyone else in the series….Ultimately, Elektra exists to sharpen Miller’s definition of Matt…Or as Miller puts it, Elektra ‘test[s] how good Daredevil is..’” She also helped reshape the Man Without Fear’s universe, as Daredevil co-artist Klaus Janson noted: “When Frank introduced Elektra in DD #168, it was the culmination of Frank’s intent to rebuild Daredevil and his supporting cast.”

But the creation of a character like Elektra had its own issues. In order to achieve what Nelson calls a “female character who would be as physically able as any male character,” Miller had to transcend comic book precedent, telling Comics Feature, “in working up a female character that is assertive, you’re working against a lot of visual conventions that are designed to present women as passive…neither the writers or the artists have really been able to handle the concept or the delivery…in a way that’s attractive and dramatic.”

Miller was not beyond using the character to manipulate his readers. Discussing Elektra’s stabbing of Ben Urich he told Sanderson, “By letting the reader get to know him and then taking him away, I got a strong emotional [mail] response and was able to turn them against Elektra.” But, as Howe notes, it was the female assassin who gripped Daredevil’sreaders and Miller knew “how popular Elektra was and how catastrophic it would be for his audience if something happened to her.”

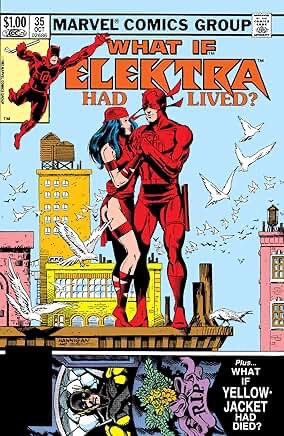

Elektra’s influence on Daredevil is perhaps clearest in Miller’s story for What If? #35, which appeared seven months after her death. In this issue, written and penciled by Miller, Matt visits Elektra’s grave as the Watcher appears to present an alternative reality in which his former lover survives. In it, she still reneges on her assignment to assassinate Foggy Nelson, but Bullseye is removed from the equation so he can’t murder her. Instead, Elektra is attacked by Kingpin’s hired thugs, whom she easily dispatches, and seeks refuge with Murdock, who has been intent on bringing her to justice. But, as Dan Seeger points out, “Presented with the opportunity to rescue Elektra, Matt Murdock does exactly that. The last glimpse of the duo is one of resplendent bliss. The grim conclusion, then, is not that Elektra’s survival precipitates a worse trajectory for her and her beloved. Instead, it is that the alternate timeline is not shared with only the dear reader… the real Matt Murdock knows that he could be living a better life than the one he is in.”

The implication of this alternate reality is that she is the reason they are both now retired, the reason Matt has refuted his roles as lawyer and vigilante. Miller seems to be saying that Elektra’s continued existence would deprive Hell’s Kitchen of its hero and the legal world of Murdock’s skills. It would mean the end of Daredevil but also the resolution of the internal conflicts his professions precipitated.

Miller would continue writing scenarios that reexamined Elektra, her fate and its consequences, returning to the character over the next ten years in Elektra: Assassin (1986), Elektra Lives Again (1990), and the reimagined Daredevil origin tale The Man Without Fear (1993-4). Paul Young sees Elektra Lives Again and Elektra: Assassin “as second chances Miller seems to feel he owed the character.” It’s also possible to view What If? #35 as serving the same function.

According to former Marvel editor Mary Jo Duffy, Miller told her in 1982 “that when he had time he was already planning a graphic novel involving Elektra…but he assured me that the graphic novel would [clarify her demise in Daredevil] and extend her story beyond her death.” Based on Miller’s description, that project was most likely Elektra Lives Again. Nelson reports that “the plot of Elektra Lives Again was originally conceived as the natural continuation of Elektra’s story as she appeared in the pages of Daredevil.”

Timothy Callahan posits that, as far as he can tell, “Elektra Lives Again was written and drawn as Miller was finishing up his first Daredevil run, around the same time as he was working on Dark Knight Returns. Fanzines and in-house publicity at the time seem to indicate a planned mid-1980s release for Elektra Lives Again.” Howe also dates the project as concurrent to Miller’s work on The Dark Knight Returns and his collaboration with Bill Sienkiewicz on the Kingpin-centered Daredevil: Love and War, while editor Ralph Macchio refers to ELA as “Miller’s long-in-production hardcover.” All five aforementioned comments indicate that the writing of What If? and Elektra Lives Againwere sequential and that the latter was conceived much earlier than its 1990 publication.

The graphic novel, published by the Marvel imprint Epic Comics, was first discussed in the letters page of Daredevil #219 in spring 1985, an issue written by Miller, in which Macchio announced two new projects from the writer, a Kingpin graphic novel eventually released as Love and War and “the long-awaited Elektra book” he was “scripting, penciling and inking.” By the end of the year, Marvel Age #36 was referring to this project as Elektra: Act of Love, one of a series of upcoming Miller releases that now also included Born Again and Elektra: Assassin.

Miller described ELA in Marvel Age #96 as “a scary action story – really a horror story.” He explained that because the tale “was removed from Daredevil comics, it grew like crazy, and became much more focused as a horror story. The goal of the whole story is to complete the portrait of Elektra’s character and to delve into the notion of someone coming back from the dead and what that would mean.”

But the narrative isn’t so much about the title character returning from the dead as insistently dwelling in Murdock’s memories, reliving an existence ultimately fated to end in her absence. Repetition becomes a motif of the tale, which Callahan calls “recursive storytelling, with Miller alluding to past events but also repeating visual patterns and narrative moments with different nightmarish interpretations.” The effect is that of a cycle continually replaying moments from the past in hope of a more favorable outcome.

Whereas the narrative of Miller’s initial Daredevil run is told objectively, Elektra Lives Again is a subjective account, a visual depiction of a fever dream and an uncomfortable and, at times, unnerving view of Murdock’s tortured psyche over the loss of his lover. Any doubt about that is dispelled by the fact that, as Timothy Callahan has noted, “the book is filled with Catholic overtones,” beginning with the subtlety of the cover illustration. Macchio recalled the design in the Elektra Omnibus, writing that the cover is “a deceptively simple piece: a white background with a single figure of Elektra and black lettering. But [the lettering] was designed just so to resemble the shape of a crucifix.”

The narrative and penciling by Miller do not engage in the surreal as they do in Elektra: Assassin so that Matt’s nightmares look and feel real while defying logic. Lynn Varley’s colors are effectively muted and restrained except for several panels in which Murdock phones Karen Page in a futile attempt to seek refuge in another old relationship, one that Page rejects outright. A one-night fling with a client proves hopeless as well, not even deserving of the respite of a brighter color palette.

Years before its publication, Marvel Age ran a panel sequence from the graphic novel that would not appear in the final product. Murdock speaks of a pain in his hand, opening it to reveal blood and a poison star thrown by Elektra that he catches in a previous dream sequence. The inclusion of this scene would have removed the line between reality and dreams; it’s replacement in the final version shows Murdock’s hand bandaged, but we don’t see the wound inflicted in the dream, its “reality” confined only to Murdock.

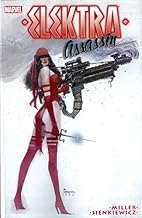

“Frank is determined to separate [Daredevil and Elektra],” editor Al Milgrom told Marvel Age in 1986. “He feels that Elektra has become too associated with Daredevil and he wants to show that she can stand on her own.” The result of this was Elektra:Assassin, an eight-issue miniseries set in the character’s past before her return to NYC and Matt Murdock.

According to Duffy, Miller approached her in 1985 about “an untold story about Elektra’s past.” Duffy revealed that “the story changed dramatically as Frank and Bill played off each other in ways that combined genius, lunacy and magic. Certain scenes and characters were dropped entirely as others were expanded,” like SHIELD agent John Garrett, who originally was to be eliminated in the second issue but became a focal point of the story by partnering with the title character. The tale gradually took on a surreal quality in both its tortuous narration and eclectic artwork that served most effectively in portraying Elektra and her demons.

Christopher Larochelle’s assessment of Elektra: Assassin, which essentially is a tale about preventing the Hand’s supreme leader, the Beast, from gaining a foothold in our world, considers it “a signpost of where comics were in 1986 and a display of just what could be accomplished within the medium.” It’s creation may also be the most revealing about Miller’s view of the character.

In a 2016 article on Elektra: Assassin, Back Issue reported Frank Miller as saying in Amazing Heroes#99, that his character “is a force of mystery throughout the entire series” and “writes herself. She surprises me continually. Part of the discipline of writing the character is trying not to understand it too well. Because then you could wind up with a character who’d just be all the things you wanted to push.”

Larochelle has noted that “throughout Elektra: Assassin there is a sort of abstraction to the way that the title character is portrayed. Oftentimes Sienkiewicz chooses to show Elektra from behind, as a faceless swirl of red cloth and feminine form. Other times part of her face is obscured, and Elektra’s red lips are one of the only clear indications that a human face is the subject of a panel.” Sienkiewicz admittedly considered her “more of an essence…than a defined person.”

In 1991, Miller called Elektra:Assassin “a story distanced in time from where I left Elektra.” He used the opportunity to retcon her origin story. As Comic Book Resources describes the modification in issue #1, “now Elektra trained with the Chaste (and was rejected by them) when she was 12 years old, years BEFORE she met Matt Murdock…” The adjustment would soon follow her into Miller and John Romita Jr.’s The Man Without Fear five-issue series, which debuted in late 1993 and was based on a television script for a possible series. As it was readying for publication, Marvel Age was reporting that film director Oliver Stone was interested in producing a movie of Elektra:Assassin, although it would be another decade before the character reached the big screen.

In 1986, Milgrom had said Elektra Lives Again “is going to be the final chapter in the Elektra saga – at least for now.” Miller would return once more to his creation in the reimagined Daredevil origin story The Man Without Fear. But Marvel wasn’t quite ready to relinquish her and gave approval to D.G. Chichester to incorporate her into his DD run. As of 1993, Murdoch was still having nightmares over the loss of Elektra. In what might be a sort of homage to the introductory splash page of issue #182, the opening of Chichester’s “Shock Treatment” (issue #314) depicts Matt dreaming of Elektra, who has returned to drive her sai into him. “The fact that it’s a dream doesn’t make it any easier,” Daredevil’s narration declares. “In a haunting way it’s even worse…in dreams there is only the trap of what might have been. And that’s a nightmare against which there is no defense.”

Chichester’s opening revery in the issue was merely a prelude to Elektra’s impending full-scale resurrection over the course of 1994-1995, first in the Fall from Grace series, then in two short back-stories in Daredevil #334 and #336, and finally in the Elektra: Root of Evil four-issue run. Young notes that “Miller has always said that he wanted Elektra to stay dead,” so Elektra’s return, Howe reports, was “much to the consternation of Miller, who’d been promised the character would not be used without his involvement.”

According to Julian Darius, “Miller’s original deal with Ralph Macchio wasn’t really that no one would use Elektra. It was that no one would bring her back except Miller.” Such an agreement may have stemmed from a combination of his awareness of what could happen if she landed in the hands of other writers/artists as well as his personal connection to his creation. When, in 1993, Marvel Age asked Miller if he was considering any future Elektra stories, he responded, “Obviously, they would have to happen in the past…but the story would have to be just dead on perfect,” admitting that “she’s nearer and dearer to my heart because I created her.”

Nonetheless, Chichester, discussing in 1998 the character’s revival in Fall from Grace, stated that Elektra was “the missing piece that clicked together all the loose pieces of the story in my head,” adding,”in my mind, it’s always been ‘her’ to whom the title refers.” For most of Fall from Grace’s seven-issue arc, a resurrected Elektra hovers on the fringes until her appearance near the end. As the Chaste proclaim, she doesn’t merely remember her past in order to not repeat mistakes, she embraces it “and, for that, she has fallen.”

While the tale occasionally flashes back to moments from Miller’s various runs, the choice to name Garrett’s attendants Frank and Bill and then have them killed early on seems motivated more by an intent to depose than to offer tribute. If boundaries were being drawn at this point, they apparently were still in effect five years later when Chichester discussed Elektra’s revival, stating, “maybe that didn’t sit well with Mr. Miller.”

Restoring Elektra to active duty in the Daredevil universe gave license to continue her adventures in Root of Evil, which used the same team of Chichester, penciler Scott McDaniel and colorist Hector Collazo. It was, in fact, an intention to reestablish her as an ongoing figure – Chichester noted in Daredevil #333 that he and his team were “firmly establishing her character as a contender for the future.”

Following the conclusion of Fall from Grace in 1994, Chichester and company offered two “teasers” in Daredevil(“Quiet Time” and “Child Care”) to demonstrate Elektra’s new identity as a violent heroine intent on defending citizens against perpetrators of crimes. Eschewing the “anti-hero” label of someone like Punisher, she seemed instead to prefer the title of “protector.” The “teasers,” consisting of only three or four pages each, served as a reminder of what the character, now front and center once again and liberated from her Assassin connections on view in Fall from Grace, is capable of and how far she would go in using her mercenary abilities to save the innocent, setting the tone for her 1995 four-issue run.

However, the reboot of the character in Root of Evil includes significant variations to her former self. Yes, she’s still a warrior trained in the martial arts, a previous lover of Daredevil, a daughter affected by the death of her father and a combatant always on the precipice of her demise. But what Chichester accomplished in bringing the character back for her own title is likely what Miller foresaw once she left his supervision.

“Elektra no longer suffers from any lack of attention,” we’re told in the first book. “She doesn’t sell death anymore. Now she gives it away.” Daredevil, in a cameo, prevents her from killing the last member of a brigade she’s battling in the issue’s opening, and there is no love evident between them, only insults and accusations. Her motivation has also been altered. Tekagi tells Elektra, “it’s about Fear. Fear that you’re no better than ordinary,” and the issues are filled with flashbacks emphasizing this.

Chichester retains several traits Miller provided for his character, including the recent retcon of her training in the martial arts at the age of 12 when she is taught by the Chaste. But, here, her unrealized intent in being a member of the Chaste influences the formation of her own team, which facilitates the third book’s battle with the Snakeroot but overlooks the character’s acceptance of/adherence to her status as a loner occasionally augmented with a temporary partnership. Elektra’s association with death is also on view here (the issues are titled “The Force of the Killer,” “Murderer’s Bible,” “Hour of the Wolf” and “She Who Slays,” we see her as a child using a graveyard as a playground, and we’re told her mother dies with Elektra still in the womb) but is unlike Miller’s treatment, which simply shrouded her in that sensibility and sat back to survey its effect on Murdock and his readers.

In 1998, Chichester defended his decision to revive the character, saying, “it was explained to me, he did have a long standing verbal agreement with Ralph Macchio (an individual, not ‘the company’) that Elektra would not be put into play providing, 1.) A story wasn’t developed that made good use of her, and 2.) That Ralph maintained control of the character. As it turned out, we came up with a story that did some things to advance the character…Ralph later lost control of the character, along with DD, making all of that agreement (not a contract, not a pact) void anyway.”

The choice to revive Elektra guaranteed her continued presence in comics. It certainly liberated her from inhabiting only dreams, nightmares, what-if scenarios and the past, but she was also disconnected from the more complex, intriguing vision of her creator, who is quoted by Howe as saying the violation of the agreement to retire her “stings like hell.”Darius has declared, “When any creator besides Miller uses Elektra, he or she owes a debt to Fall from Grace and that first Elektra series.” Yet, if, as Garski and Yen note, “her fight for identity has never been easy or clean,” post-Miller portrayals of the character have made that task even more challenging, right down to the recent Funko Pop rendering of Elektra which, when juxtaposed against her image on the Coke can and her current comic book appearances as the female Daredevil, offers a clear picture of an identity in crisis.

Sources

Callahan, Timothy. “Frank Miller’s Long Goodbye: ‘Elektra Lives Again’”Comic Book Resources, 2 December 2013. retrieved from cbr.com.

Chichester, D.G., Scott McDaniel and Hector Collazo, et.al. “The Force of the Killer.” Elektra Root of Evil #1, March 1995.

Chichester, Dan, Scott McDaniel and Hector Collazo. Fall from Grace. New York: Marvel Comics, 1993, 1994.

Chichester, D.G. “Elektra Report.” Daredevil #333, October 1994, n.p.

Chichester, D.G. “Shock Treatment” Daredevil #314, March 1993, 1-2.

Collazo, Hector. “Elektra Report.” Daredevil #337, November 1994, n.p.

Cronin, Brian. “Daredevil: What is Elektra’s True Origin.” Comic Book Resources 14 June 2024. retrieved from cbr.com.

Darius, Julian. “What Fall from Grace? Reappraising the Chichester Years,” in The Devil is in the Details: Examining Matt Murdock and Daredevil, Ryan K. Lindsay (ed.), Edwardsville, Illinois: Sequart Research and Literacy Organization, 2013.

Duffy, Mary Jo. “Introduction,” in Elektra by Frank Miller and Bill Sienkiewicz Omnibus. New York: Marvel Worldwide Inc., 2016.

“Elektra.” The Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe, D-G, #4, April 1983, 6.

Fisch, Sholly. “The Return of Frank Miller.” Marvel Age #36, March 1986, 18-23.

Garski, Larisa A. and Jennifer L. Yen. “Elektra: Portrait of the Assassin as a Young Woman,” in Langley, Travis (ed). Daredevil Psychology: The Devil You Know. New York: Sterling, 2018.

Howe, Sean. Marvel Comics: The Untold Story. New York: Harper, 2012.

Larochelle, Christopher. “Elektra: Assassin.” Back Issue #90, August 2016, 2-10.

Lindsay, Ryan K. “Blind Dates and Broken Hearts: The Tragic Loves of Matthew Murdock,” in The Devil is in the Details: Examining Matt Murdock and Daredevil, Ryan K. Lindsay (ed.), Edwardsville, Illinois: Sequart Research and Literacy Organization, 2013.

Machio, Ralph. “Resurrections,” in Elektra by Frank Miller and Bill Sienkiewicz Omnibus. New York: Marvel Worldwide Inc., 2016.

Miller, Frank, John Buscema and Gerry Talaoc. “Badlands.” Daredevil #219, June 1985.

Mithra, Kuljit. “Interview With D.G. Chichester.” Daredevil: Man Without Fear, February 1998. retrieved from man without fear.com.

Nelson, Brian. “Elektra Lives Again.” Marvel Age #96, January 1991, 8-9.

Sanderson, Peter. “The Frank Miller/Klaus Janson Interview.” The Daredevil Chronicles, February 1982, Albany: FantaCo Enterprises, Inc., 9-27.

Seeger, Dan. “My Misspent Youth — What If? #35 by Frank Miller.” Coffee for Two, 17 February 2021. retrieved from coffee-for-two.com.

Young, Paul. Frank Miller’s Daredevil and the Ends of Heroism. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2016.

Related Articles

Daredevil @ 60: Part 1 – Hell’s Kitchen

Daredevil @ 60: Part 2 – The Netflix Series

Daredevil @ 60: Part 3 – The Charles Soule Run (2015-2018)

Leave a comment