May 1, 2025

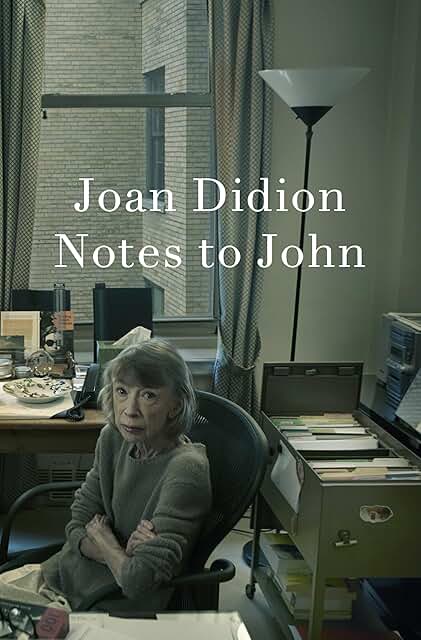

Joan Didion’s Notes

A Commentary

When you consider it, deceased writers are never really gone. Their books have a chance of carrying their names well into the future, of providing that immortality sought by many. And then there are the archives, those early drafts and unpublished works sitting in drawers and boxes that somehow didn’t pass muster. Rightfully or not, some receive publication, others are relegated to scholars and biographers to sift through. And, occasionally, some may be debated as too private to merit sharing.

The fact that the recent publication of Joan Didion’s Notes to John incorporates all three of the above-mentioned posthumous scenarios shouldn’t be too surprising. A new work by Didion is a welcomed literary event, as is the surviving archive of her and her husband, John Gregory Dunne, recently made available to the public by the New York Public Library and the source of the new book. And while the material comprising Notes to John may constitute eavesdropping, containing as it does private moments laid bare, similar content had already been addressed in the highly personal non-fictions The Year of Magical Thinking and Blue Nights, Didion’s final two books. These essentially grant permission for the publication of the new release.

The book, consisting of the author’s notes on her psychotherapy sessions at the turn of the 21st century, is culled from 150 unnumbered pages, we are told, discovered after her death in 2021. In its April excerpt of the release, the New Yorker observed, “She recorded her thoughts with the cool, forensic clarity she was known for.” But there is so much more that is achieved in the design and the writing. The book is a narrative beginning in medias res and covering just over a year, its text forming a dialogue among three people disconnected in time and space, much like the disembodied voices of Samuel Beckett’s later plays. Didion is writing to her husband about her conversations with therapist Dr. Roger MacKinnon, recounting those moments in a swirl of voice shifts. She positions herself as the link between past, present and future in these ‘chapters,’ not unlike her placement as author in novels like Democracy. Even in journaling, Didion never strayed far from her art.

As the primary voice, she allows the sessions themselves to provide, if any, the drama and resulting catharsis. “Re not taking Zoloft, I said it made me feel for about an hour after taking it that I’d lost my organizing principle,” she explains at the start of the first entry in December 1999. Things transition into a conversation about her anxiety and how it relates to her and her husband’s adopted daughter Quintana, whose death would be mourned in Blue Nights just as Dunne’s was in The Year of Magical Thinking. “She once described me, as a mother, as ‘a little remote,’” Didion says. Her frankness elicits the question, “You don’t think she saw your remoteness as a defense?”

Discussions also touch on her professional life, a concern as she entered the new century. In late 2000, she says of her screenwriting work with Dunne for Hollywood films, “we had for all intents and purposes shelved the movie business.” In discussing what became Where I Was From, she maps out her plans, which include taking “a couple of long pieces I’d done about California and use them…as notes for an extended essay or book about California.” It is “meaningful work,” she is told, “crucial to your own survival.” She is also cautioned, “It’s not selfish.”

The other voice in Notes to John, the one questioning, cautioning and explaining, is that of MacKinnon, the psychoanalyst Didion began seeing in November 1999. MacKinnon, who died in 2017, was recognized as a prominent New York City psychiatrist, psychoanalyst and author whose private practice spanned six decades. His dialogue in Notes to John appears as quoted material and strikes a delicate balance between professional and informal. Discussing a hip injury, Didion wonders if it “did something to your brain” to make you feel fragile. MacKinnon’s response comes from personal experience: “I’d never before been nervous walking around this neighborhood after dark. But on crutches I was. I felt like prey.” He explains, “it affects your self-image in a negative way.”

The third piece in this triangle is Dunne. His voice is largely silent here (he is paraphrased in the entry for the June 7, 2000 session he attended), but his presence is consistently affirmed each time his wife addresses him, explains things to him or seeks an understanding from him. He is there to support and, at times, absolve, but mostly he is there to listen.

In The Year of Magical Thinking and Blue Nights, we are given accounts of and reckoning with indisputable tragedies. Didion biographer Tracy Daugherty has even observed that in Where I Was From “we might well be witnessing an irreparable tragedy” concerning the contemporary fate of towns in California, a state whose mythology intrinsically intertwines with that of Didion’s family and identity. It is possible, then, to see these three works collectively as a trilogy about the type of loss that cannot help but impinge on the self-image of its author. It is also possible to see Notes to John as the earliest and perhaps most revealing drafts of Didion’s late-period writings.

Related Article

Leave a comment