November 1, 2024

Dylan: Tour ’74 Revisited

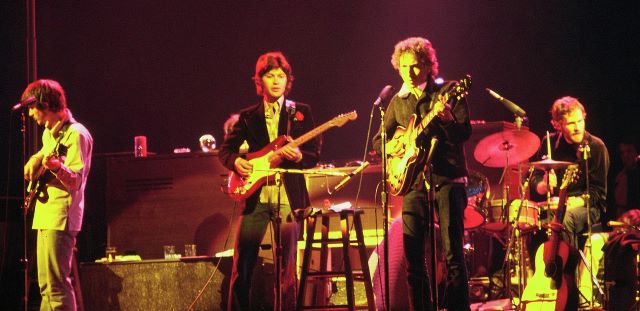

The 1974 Live Recordings, the recently released 27-disc box set of Bob Dylan and the Band’s tour a half-century ago, has a story to tell, its narrative steeped in Dylan’s acclaimed return to the road after eight years. And its earliest shows and news coverage, particularly those in Philadelphia, offer a fairly prophetic vision of what would unfold over six weeks in 1974.

It’s time to finally put aside Before the Flood, until now the only official document of Tour ‘74. The new box set contains a much more vast and intriguing view of the tour’s musical performances in excellent sound quality, collecting twenty-six of the forty shows from the tour. True, the set does not include the January 10 Toronto show at which the only ever live version of “As I Went Out One Morning” was performed, but fans can seek out the audience recording of the concert as well as audience tapes of the January 23 Memphis show, which featured a one-off “Fourth Time Around” as well as the February 4 St. Louis afternoon performance boasting the only “Desolation Row” and “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” and the February 6 Denver afternoon concert with the sole “Visions of Johanna” of the run.

According to the Best Classic Bands website, “At the outset, the 1974 Tour was captured on a stereo soundboard mix on both 1⁄4” tape and cassette.” Near the tour’s conclusion, multitrack recordings were commissioned for the live album, and the new box “includes it all: the cassettes and 1⁄4” tapes, and the shows that were recorded on 16-track tape, newly mixed for this collection.”

Following the 1965-1966 tours with the Band (then The Hawks), Dylan entered his reclusive period in Woodstock, New York, and The Band followed. Together they made the home recordings of the Basement Tapes and occasionally ventured out for a performance. Except for the 1971 Concert for Bangladesh, Dylan’s onstage appearances at the NYC Woody Guthrie Memorial Concert in 1968, the Edwardsville, Illinois Mississippi River Festival and Isle of Wight Festival in 1969, and a New Year’s Eve performance in 1971/1972 had been with the Band as accompanists.

By early fall 1973, they had collectively transplanted themselves in California, where circumstances brought them into contact with David Geffen, chairperson of Elektra-Asylum Records. According to Howard Sounes, they “came to a loose agreement whereby Bob would not re-sign with Columbia when his current contract expired, but would make one studio album for Asylum, backed by The Band…Geffen would promote the first album by staging a comeback concert tour for Bob and The Band for which Bob would receive most of the profits.”

Rolling Stone writer Ben Fong-Torres reported that Dylan originally envisioned “a chance to hit maybe a dozen cities just to get out and play.” When promoter/tour organizer Bill Graham explained the logistics of such a small tour would be impossible, Dylan acquiesced And, with that, the tour was arranged for the opening months of 1974.

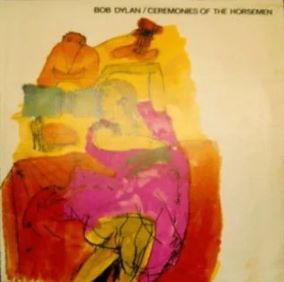

Graham started reserving concert venues “without telling owners the name of the show’s star,” according to Edith M. Lederer. In early November 1973, the tour was announced and, on December 2, 1973, ads appeared in newspapers saying simply “Dylan/The Band,” along with details on how to mail order tickets. Newsweek explained the mail order process was chosen because “Dylan wanted all age groups to have an equal chance to hear him, not just the kids who would stand in line at the box office for days before.”

According to Lederer, there was another reason for the mail-order process and limit of four tickets per customer – “to discourage scalpers.” But scalping ensued nontheless. The Philadelphia Inquirer reported that scalped tickets were going for fifteen dollars apiece outside the Spectrum arena. Two days before the first concert in the City of Brotherly Love, the Philadelphia Daily News was saying that the Sunday January 6 matinee and evening concerts and Monday January 7 night show had nearly sold out; surprisingly, by the start of the first concert, Fong-Torres noted, tickets for the third show were still available.

Once the ads had appeared, the numbers took over. A 25-city tour over 6 weeks was pared down to 21 cities, with, according to Rolling Stone, tickets running “$6.50 to $8.50 in ‘primary markets’ and $5.50 to $7.50 in ‘secondary markets.’” Prices ascended to “as high as $9.50 and $10.50,” Newsweek reported. With 658,000 seats available for the tour, “Geffen estimated 2 million to 3 million envelopes [with money orders] were sent back.” The publication predicted “the concerts will gross a cool $5 million,” up from Rolling Stone’s projection several months earlier that the run would gross “between $4 and $4.5 million.”

Near the end of 1973, Anthony Scaduto wrote, “Dylan had announced he would start his own record label, Ashes and Sand, to be distributed by Elektra-Asylum Records.” A new album was recorded with the Band, its release to coincide with the start of the tour, but changes with the cover delayed distribution until January 17. By the Philadelphia stopover, there was still uncertainty as to the LP’s title.

On the morning of the first two Philly shows, an article from the Chicago Tribune Service appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer, reporting that the upcoming new Dylan album was “to be titled Love Songs,” adding that another source “says it’s to be called Ceremonies of the Horseman.” The night prior, reporter Patsy Sims attended a dinner in honor of The Band at the Le Champignon restaurant where several members of the ensemble “brought out a tape recorder to give us a preview of their album that’ll be released in a week or two – Ceremonies of the Horsemen or whatever it’s going to be called…” By mid-January it appeared in record bins as Planet Waves on Geffen’s Asylum Records, the idea for the Ashes and Sand label having been dropped. Dylan told Fong-Torres, “I advised myself it was a good thing, and then I advised myself that it wasn’t. I just didn’t need it.”

The album ultimately took a thrashing from critics, mostly for not being Highway 61 Revisited or Blonde on Blonde, but so had the previous four releases. Philadelphia writer Jonathan Takiff, who was ecstatic about the first Philly concert in 1974, dismissed Dylan’s recent recordings by saying he had “not turned out a meaningful album in four years.” Reviewers of Planet Waves felt the trend was continuing. The New York Times’ take on Planet Waves was that “the worship of Dylan seems more like the start of sixties nostalgia than an attitude to be justified by his current work.” And so on. Fans, on the other hand, propelled the LP to Number One on the Billboard album chart within two weeks of its release, a first for Dylan.

By the Philadelphia stopover, the sets were still in a state of flux but beginning to coalesce into what became the tour standard. At the first concert in Chicago, Dylan remained onstage for most of The Band’s performances. By the second night, it became what the Philadelphia Daily News called, “a highly polished, adroitly programmed series of mini sets.” The shows had been divided into an opening six-songs by Dylan/Band, a Band set before Dylan returned for three songs followed by an intermission, a Dylan acoustic set, another Band interlude and a finale by all. The concerts favored a fashionably late start time over what was listed on the tickets. There was a thirty-five-to-forty-minute delay before both the Sunday afternoon and evening concerts on January 6, and the fashionably late starts continued.

During the Philly shows, the Chicago opener “Hero Blues” was replaced by “Ballad of Hollis Brown,” which was itself replaced by “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35.” “Tough Mama” and “Song to Woody” received their final performances of the run, and “Mama You’ve Been on My Mind” appeared and disappeared. “Most Likely You Go Your Way and I’ll go Mine,” was only performed as an encore, having yet to take its place as the opener as well.

The Tour ‘74 stage sported a down-home look that Robert Shelton said Dylan “had approved…with a bunk bed, a sofa, a Tiffany lamp, a clotheshorse and a few candles” reportedly sitting on a barrel, in addition to a rug, hat-rack and stool. The look changed a bit by Philly, with Stephen Pickering reporting that the bunk bed was no longer part of the décor, but “a white cloth-covered table with wine [and] glasses and a large pitcher” were.

Dylan’s Philadelphia concerts were his first at the Spectrum, which had opened in 1967 with a capacity of 18,989. It’s easy to measure the growth of his popularity by the string of venues he played over the previous decade. His first concert in the City of Brotherly Love had been on May 3, 1963 at the Philadelphia Ethical Society’s 300-seat Rittenhouse Square auditorium. According to Clinton Heylin’s chronology, his next two Philly appearances were at the 1,900-seat Town Hall on October 25, 1963 and in late September 1964, where an audience member recorded the latter show for posterity. In 1965, he played the 12,000-seat Convention Hall on March 5, but it was a joint tour with the highly popular Joan Baez that required a larger venue to accommodate the billing. Philly would not witness the first electric tour later that year and had to wait for Dylan and The Band to perform a pair of concerts at the 2,500-seat Academy of Music on February 24 and 25, 1966. And then, of course, there was the definitely almost maybe near-appearance at the 1972 Philadelphia Folk Festival, the story of which can be found in the “Evening Shades of Gray” post on this site.

During his brief 1963 stay in Philadelphia, Dylan had played dodgeball with Tossi and Lee Aaron’s daughters. The Aarons, according to Takiff, “put up Dylan for the night” after his first Philly concert and “were admittedly bowled over by Bob Dylan’s boyish charms.” In 1974, the boyishness was gone, as poet Michael McClure noticed: “Dylan a grown man…the nasal boy’s voice replaced by a man’s voice.” Also gone were the dodgeball games, replaced by ice skating at the Penn Center Rink where, according to Sims, “those who skated right by him …didn’t know it because he had on a Russian hat and a nose muff pulled up to his eyes.”

But Dylan couldn’t hide at the concerts. Other than during The Band sets, he was center stage, commanding the attention of nearly 20,000 people. Still, some fans worried. “Dylan was in danger of disappearing into his own creation,” McClure wrote after attending a Philadelphia performance. “He had spawned so many followers, imitators and Dylan-influenced groups and movements that he stood in danger of blending in among his own offspring and hybrids…” Three weeks later, Michael Gross experienced Dylan’s disappearing act at Nassau Coliseum on a literal level: “Dylan appeared, and though the crowd roared, he could hardly be seen or heard.” A few days later, in Madison Square Garden, Daniel Mark Epstein had another perspective on the same theme. “The big difference between seeing Bob Dylan in 1963 and seeing him in 1974,” he wrote, “is that now you could hardly see him…he appeared and disappeared without ceremony.”

Such matters didn’t concern reviewers of the shows. Most reveled in the singer/songwriter’s return, showering him with praise and imbuing him with abilities beyond his musical talents. In “the early moments of a brand-new year which arrived with the prospect of hard times ahead, Dylan and the Band brought their magic show to town,” read the opening of Jack Lloyd’s Philadelphia Inquirer review. Takiff’s Daily News review summed up Dylan’s afternoon acoustic set on January 6 by observing “Dylan re-appeared in work shirt and vest, with acoustic guitar and harmonica, to deliver a set of protest ballads from the early 1960s that sealed our devotion.” Lloyd was convinced the “the audiences were there to hear the old songs.” Takiff concluded his piece by addressing Dylan: “Welcome back, old friend.”

Discs 3 to 5 of The 1974 Live Recordings feature the Philadelphia concerts, and you can hear the tour settling in for the remaining thirty-five shows. The run was certainly an icebreaker for Dylan, who would re-sign in early August with Columbia and return to form as well as to New York City. By the end of 1974, he would record Blood on the Tracks, some of it twice. Tour ’74 gradually became a distant memory, its roar quieted as the media and fans no longer had any say in what the future held for Dylan. As Ralph J. Gleason had noted earlier that year, “it is the artist, not the audience, who defines, in the end, the artist’s role.”

My article “Ceremonies of the Horsemen,” which examines the tour in more detail, will be published next month in The Bridge, whose website can be accessed by clicking here.

Sources

Alterman, Loraine. “Dylan is His Own Dilemma.” New York Times, 20 January 1974. retrieved from nytimes.com.

Best Classic Bands Staff. “3rd Track Shared from Bob Dylan and The Band Massive Live 1974 Set.” Best Classic Bands, 6 September 2024. retrieved from bestclassicbands.com.

Epstein, Daniel Mark. The Ballad of Bob Dylan: A Portrait. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2011.

Felton, David. “Dylan, Band Reunion: Graham Handling 25-City Tour; Elektra-Asylum Said to Have Inside Track on Album.” Rolling Stone, 6 December 1973, 17.

Fong-Torres, Ben. “Dylan: A Restless Farewell to Tour ’74.” Rolling Stone, 28 March 1974, 16-18.

Fong-Torres, Ben. “Dylan Opens to a Hero’s Welcome” in Knocking’ on Dylan’s Door: On the Road in ’74. New York: Pocket Books, 1974.

Fong-Torres, Ben. “Knockin’ on Dylan’s Door.” Rolling Stone, 14 February 1974, 36-41, 44.

Gleason, Ralph J. “Like a Rolling Stone, Again.” Rolling Stone, 28 March 1974, 14-15.

Gross, Michael. Bob Dylan: An Illustrated History. New York: Tempo Books, 1980.

Hertzberg, Hendrik and George Trow. “Dylan.” The New Yorker, 11 February 1974. Reprinted in Studio A: The Bob Dylan Reader, Benjamin Hedin (ed.), New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2004.

Heylin, Clinton. Behind the Shades: The 20th Anniversary Edition. London: Faber and Faber Ltd., 2011.

Heylin, Clinton. Bob Dylan: A Life in Stolen Moments, New York: Schirmer Books, 1996.

Hoskins, Barney. Across the Great Divide: The Band and America. New York: Hyperion, 1993.

Lederer, Edith M. “The Story Behind Dylan’s 1974 Tour.” Associated Press, retrieved from Philadelphia Inquirer, 5 December 1973, 14-A.

Lloyd, Jack. “Dylan Comes Back to Life, and Fans Scream for More.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 7 January 1974, 6-B.

Lloyd, Jack. “Dylan Has Come and Gone – But Wasn’t It Beautiful?” Philadelphia Inquirer, 13 January 1974, 8-H.

McClure, Michael. “The Poet’s Poet.” Rolling Stone, 14 March 1974, 32-34.

Orth, Maureen. “Dylan – Rolling Again.” Newsweek, 14 January 1974, 46-49.

Pickering, Stephen. Bob Dylan Approximately. New York: David McKay Company, Inc., 1975.

Scaduto, Anthony. Bob Dylan: An Intimate Biography. New York: Signet, 1973.

Shelton, Robert. No Direction Home: The Life and Music of Bob Dylan. New York: Ballantine Books, 1986.

Sims, Patsy. “Mistaken Identity: Confessions of a Non-Groupie.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 13 January 1974, 8-H.

Takiff, Jonathan. “Mellow Dylan Returns to Wish Us Well.” Philadelphia Daily News, 7 January 1974, 22.

Takiff, Jonathan. “St. Dylan’s’ Return Stirs Memories of the Man.” Philadelphia Daily News, 4 January 1974, 25.

Van Matre, Lynn. “For Dylan Fans, Memories Are Almost Medicinal.” Chicago Tribune Service, reprinted in Philadelphia Inquirer, 6 January 1974, 6-I.