July 7, 2025

Guitar Tales: John McLaughlin and Jesse Ed Davis

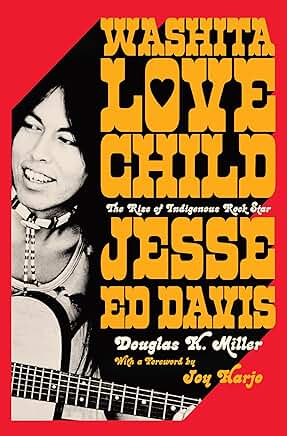

Books on music, art or film should have the power to return the reader to the subject itself, the albums, artworks or movies written about. They should provide an excuse for us to reengage with those works, maybe reevaluate them, and perhaps shed some light on why they were meaningful to us at some earlier stage in life. Not every book manages to accomplish this, so it’s refreshing to find that two recent tomes, Walter Kolosky’s Mahavishnu Memories and Douglas K. Miller’s Washita Love Child, provide an incentive to revisit the early works of guitarists John McLaughlin and Jesse Ed Davis.

Kolosky’s book is a fascinating read as a tour biography. It’s as much about guitarist John McLaughlin’s Mahavishnu Orchestra’s 1971-1973 road history as it is about the venues that booked such acts and the reviewers who assessed the performances. This was was an era of mind-boggling bills that would have acoustic solo performers opening for the high-volume Mahavishnu or the Orchestra opening for lighter-weight acts like T. Rex or even McLaughlin’s group sandwiched between two unlikely bands. The book’s examination of record company marketing and the logistics for booking colleges, clubs, arenas and festivals at the time charts the gradual rise in popularity of McLaughlin’s fusion lineup in two-and-a-half years. The research is most impressive, as is the readability.

Readers of this 500-page book will be tempted to at least re-explore Mahavishnu Orchestra’s debut The Inner Mounting Flame, its follow-up Birds of Fire and possibly some live soundboards like the 1972 Cleveland show, but there are other early albums by McLaughlin just as worthy of review on a journey like this. Many listeners at the start of the 1970s may have first encountered the guitarist as a sideman/band member on significant projects like Jack Bruce’s Things We Like,” Tony Williams Lifetime albums and Miles Davis’s In a Silent Way, but the real early gems are Extrapolation and My Goals Beyond.

Extrapolation is a quieter, less frenetic, non-fusion McLaughlin, occasionally solo acoustic but mostly with a band featuring drummer Tony Oxley, bassist Brian Odgers and saxophonist John Surman, who serve up a highly empathetic backing for their host’s eclectic jazz compositions and varied performances. The album, produced by pop mogul Giorgio Gomelsky, first appeared in the U.K. in 1969, its U.S. release following three years later after the success of the Mahavishnu Orchestra.

The 1971 album Goals is a meditative soundscape split between two extended ensemble performances and a collection of acoustic guitar tracks that highlight the gentler side of McLaughlin’s playing. The album includes future Mahavishnu members Billy Cobham and Jerry Goodman along with saxophonist Dave Liebman and bassist Charlie Haden. And it’s as far from Mahavishnu Orchestra’s intricately electric barrage as you can get. Yet, depending on your tastes, it may be preferable for its intimacy.

Miller’s Jesse Ed Davis biography, well-written and impeccably researched, is a nearly 400-page account of the guitarist’s life that neither sensationalizes nor trivializes the traumas of growing up as an Indigenous in Oklahoma and, later in life, coping with substance abuse. But Miller never divorces Davis from his passion for music and presents his life as a series of events always anchored by what he listened to, created and played. And, as with Kolosky’s book, there’s an inclination to revisit the recordings.

Davis’s preferred electric guitar style is void of McLaughlin’s jagged edges and high-velocity runs. His playing is soulfully informed by the blues, but he was also a practicer of Miles Davis’s concept of knowing when not to play, when silence is just as effective and tasteful as the selection of notes on offer (just listen to his fills on Jackson Browne’s “Doctor My Eyes”). The allure of his tone (“playing through an incredibly loud amplifier, but with an incredibly light touch,” Miller reports), country-style note-bends and occasional jazz touches, echoing his love of big bands, are incomparable, and they can be found throughout his tenure with Taj Mahal’s group, particularly on the 1969 Giant Step album. That release features Taj and his accompanists’ take on the Band’s interpolation of Andre Williams’s “Bacon Fat,” a slow-burn blues with a sweet-sounding turnaround and solo courtesy of Mr. Davis.

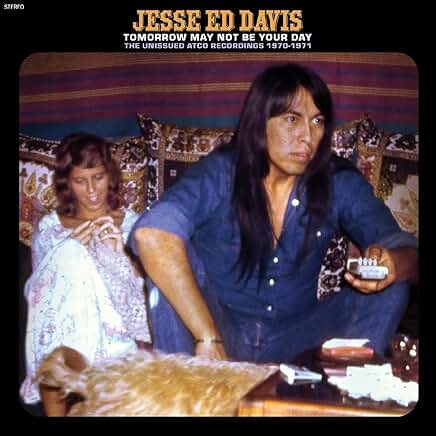

It was in 1971 that Davis caught a lot of people’s attention with session work for Bob Dylan’s “Watching the River Flow” and “When I Paint My Masterpiece,” as producer and player on Gene Clark’s White Light album, in his appearance at George Harrison’s Concert for Bangladesh and with his first solo album, Jesse Davis, which was representative of the music the guitarist loved, even if it was short on Davis’s guitar solos. His generosity as a leader toward his sidemen, in particular Eric Clapton, led to spotlighting their playing and relegating his own role to comping as part of the rhythm section. That was corrected on Ululu and Keep Me Coming, but Davis was one of those guitarists whose playing, whether it was lead or rhythm, was always a masterclass in finesse. Still, for anyone looking to hear a healthy dose of his lead work, the new release Tomorrow May Not Be Your Day – The Unissued Atco Recordings 1970-1971 is a must.

In part, Tomorrow contains alternate takes of album material, but the real treasures are the unreleased instrumentals and jams that display Davis’s six-string prowess. His slide work on “Kansas City” and a sublime rendition of Dylan’s “Love Minus Zero/No Limit” leaves the listener wanting more than just the several minutes offered by each, while “Slinky Jam” is highlighted by trademark solos. You can hear the live studio performances on the instrumental basic tracks, particularly “Kiowa Teepee,” an early, powerful take of “Washita Love Child” that should have made the cut. More than a few moments like this on Tomorrow serve to abet the biography.

There’s a necessity for archival releases like this as well as for books like Kolosky’s and Miller’s and the information they convey and the lives they examine. But they are also chronicles of an era of music that has already begun fading from view in the first quarter of the 21st century. Releases like these have a continuing purpose – they are, by their nature, the markers that remind the world of what once was and what shouldn’t be forgotten.

Leave a comment